When this product arrived in the US in the 1870s, the farmers of much of America were outraged.

How could the US government allow the sale of something that not only hurt their profits but also was so obviously bad for people? The product was a threat to the American Farm, they argued. The sale of it flew in the face of the moral fabric of the country! What type of world would allow such an evil to be for use by any right-thinking American? Even the governor of the state of Minnesota joined their campaign against this product; he labeled it an “abomination” created by “depraved minds” who had designs of killing the American farmer’s way of life. The politician bemoaned the product while he heaped praise upon the “wholesome” and “sweet” products of the farm.

Something had to be done, obviously. Yet, the poor people of the cities absolutely loved the product; they couldn’t get enough of it. And there you have it, in many ways. The divide between a rural perspective verses an urban outlook has long been a staple of American culture and politics and remains one to this day. You hear about the depravity of the cities–filled with the “evils” of foreigners, those Americans of color, and the allure of “sin”–verses the sanctity, the almost sacred nature, of the image of rural America. The divide over this product was part of that ongoing urban/rural split.

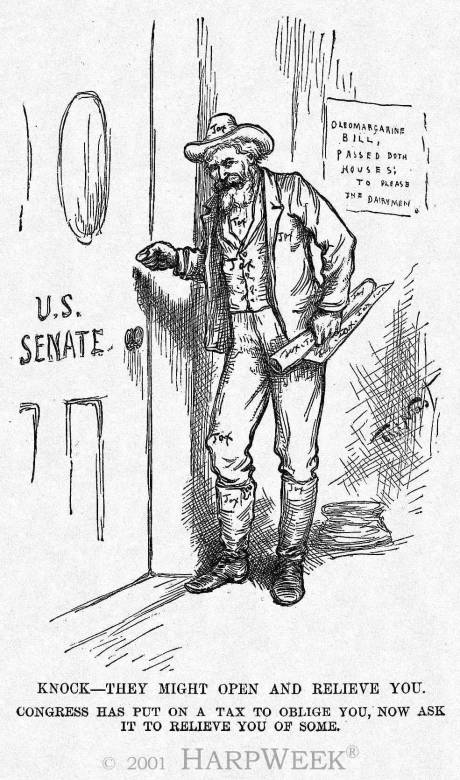

So, in order to combat the evils of this product (and since the rural establishment couldn’t outright ban it legally), they tried to tax the hell out of it in an effort to limit the city dwellers’ access to it. The sponsor of the tax bill in congress, a senator from Wisconsin, said that the product he was targeting was the product of “death” and lacked the “natural aroma of life and health” and filled with “chemical tricks” designed to hurt all right-thinking (read: rural) Americans. But it didn’t slow the purchase and consumption of the product by those in the cities. In fact, within a few years of being introduced into the US, this item was produced by over 40 different companies in an effort to meet demand. And, as the 1800s drew to a close, the cities began to have more and more residents, scaring the rural bloc even more.

A public relations effort began designed to scare people away from the product. Cartoons were commissioned by rural groups that portrayed the manufacturing process for the product and showed “foreign elements” dropping poison, garbage, and even rats into the vats in which the product was made. According to an article in one magazine, this disinformation campaign strongly hinted that users of the product would come down with diseases and cancer and even mental illnesses.

Some states with a majority rural (meaning mostly farmers) population even passed laws either outlawing the use of the product or at least imposing clear labeling on the packaging of the product detailing its potential dangers. Wisconsin, for example, had such laws on their books until the late 1960s, laws that provided for stringent restrictions on how the product would be sold. But, time changes things. Shortages in farm products caused by the first world war, then the Great Depression, and then World War 2 all served to make this product not only acceptable to all Americans but also preferred by most–even most rural Americans as well.

Who could’ve guessed that the introduction of margarine in the US would have caused such a dramatic reaction?