I don’t believe in curses. Cursing–yes, but curses, no. However, some events and occurrences seem to be more than mere coincidences. There’s the supposed curse of King Tut’s Tomb; several people associated with the discovery of that important archaeological site are supposed to have died under mysterious circumstances. There’s the Hope Diamond curse that says people associated with that famous jewel also either received terrible luck afterward or perished under strange conditions. Then there’s the curse of Tenskwatawa.

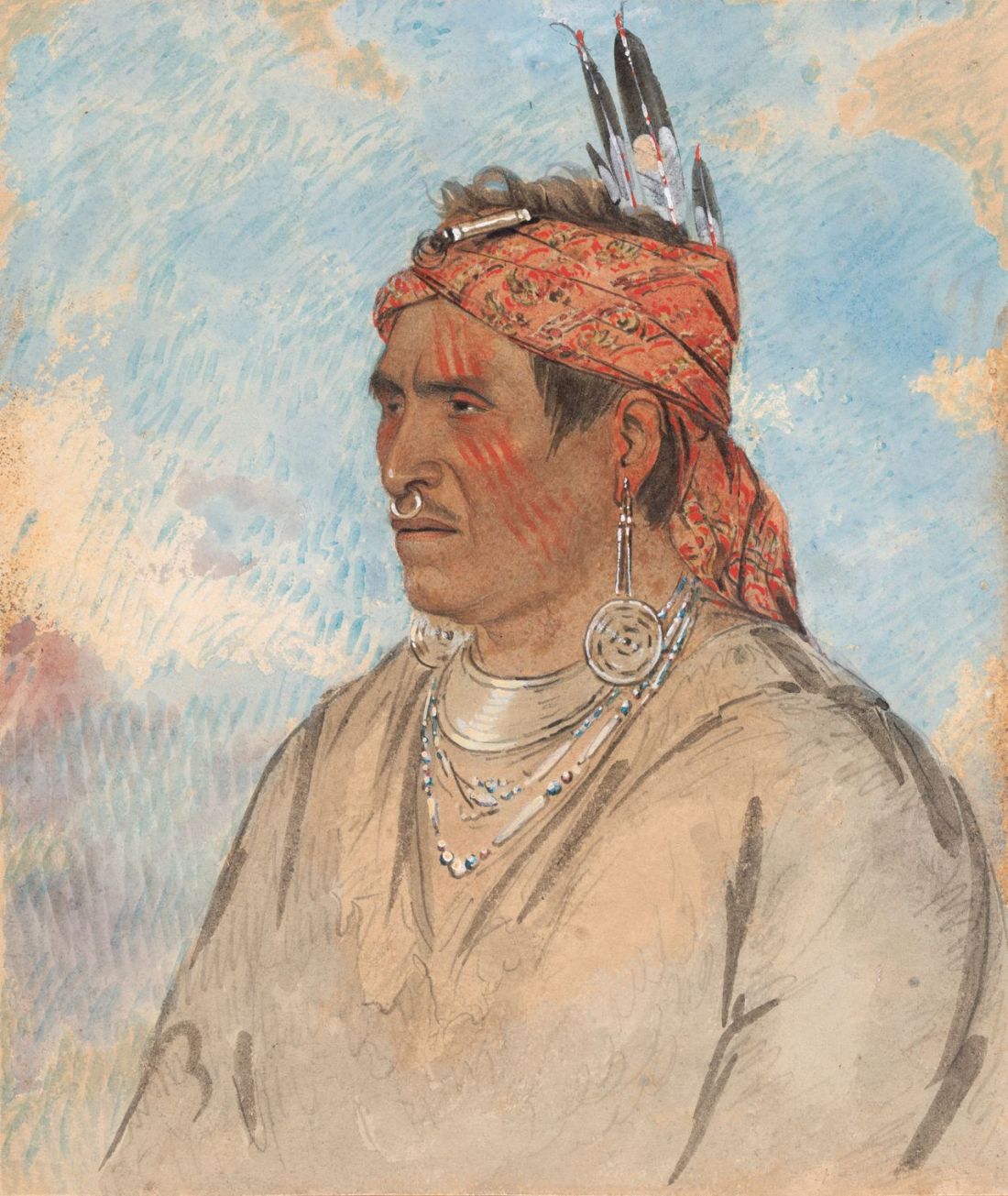

Tenskwatawa was a Native American religious leader or holy man. He made prophecies regarding his tribe, the Shawnee, as the American government made increasingly aggressive moves into Shawnee territory in the earl 1800s. The horrible history of how the American nation broke treaty after treaty with native tribes is the stuff of volumes of books and dissertations. However, for our purposes, please know that Tenskwatawa led a movement, along with his brother, to fight the American aggression.

Tenskwatawa’s message to his tribe was that they should not only fight against the Americans, but that they should also reject American culture and practices. In many ways, his preaching was a native conservative reaction to the changes that were taking place in Shawnee culture during that period. He advocated a return to Shawnee traditions and practices that would somehow channel, Tenskwatawa said, the sprits of their ancestors to defeat the encroaching Americans.

The Shawnee went to war. Led by Tenskwatawa and his brother, and joined by other native tribes who shared the Shawnee anger at the American lies and treachery, the natives made several attacks on American outposts on the frontier. The American governor of the Indiana Territory, Governor William Harrison, asked for and received permission to move against the native confederated forces. Governor Harrison believed that the only way to treat the natives was by a show of strength. In the fall of 1811, the two sides met in battle in what is now northwestern Indiana.

The native alliance lost the battle, and many historians point to this as a turning point in the dissolution of the native resistance movement east of the Mississippi River. Tenkswatawa’s reputation suffered, and his brother was killed in battle against the Americans two years later. You know that brother: Tecumseh.

And Governor Harrison parlayed his victory over Tenskwatawa into a later political career. He became known as Old Tippecanoe–the name by which the battle came to be known. Harrison ran for President in 1840 with John Tyler as his running mate under the slogan, “Tippecanoe and Tyler, too!” and won the election. However, only a few weeks after being sworn in, Harrison died. Some people whispered that the President’s death was due to a curse put on him by Tenskwatawa. The prophet’s anger at the loss of the battle and the destruction of his alliance and movement is said to have been the reason he summoned the curse on his victorious foe.

In fact, the curse was supposed to have been on Harrison and all like him who were elected in years ending in ‘0’ such as Harrison had been in 1840.

That’s laughable, right?

Well, after Harrison, the next president elected in a year ending in 0 was Abraham Lincoln in 1860. After that, James Garfield won in 1880. Garfield, too, was assassinated. Then, in 1900, William McKinley was re-elected–and was shot to death a year later. Warren Harding, who won election in 1920, died from mysterious circumstances in 1923. When Franklin Roosevelt died in 1945, people noticed that he, too, was elected in 1940 and died in office. Finally, John Kennedy, who won his term in 1960…well, you know what happened there.

But then, this supposed curse simply…ends. Ronald Reagan, first elected in 1980, was shot while in office but survived. George W. Bush, elected in 2000, had a grenade thrown at him in 2005, but the device failed to detonate. And Joe Biden, elected in 2020?

Perhaps Tenskwatawa’s wrath is slaked.