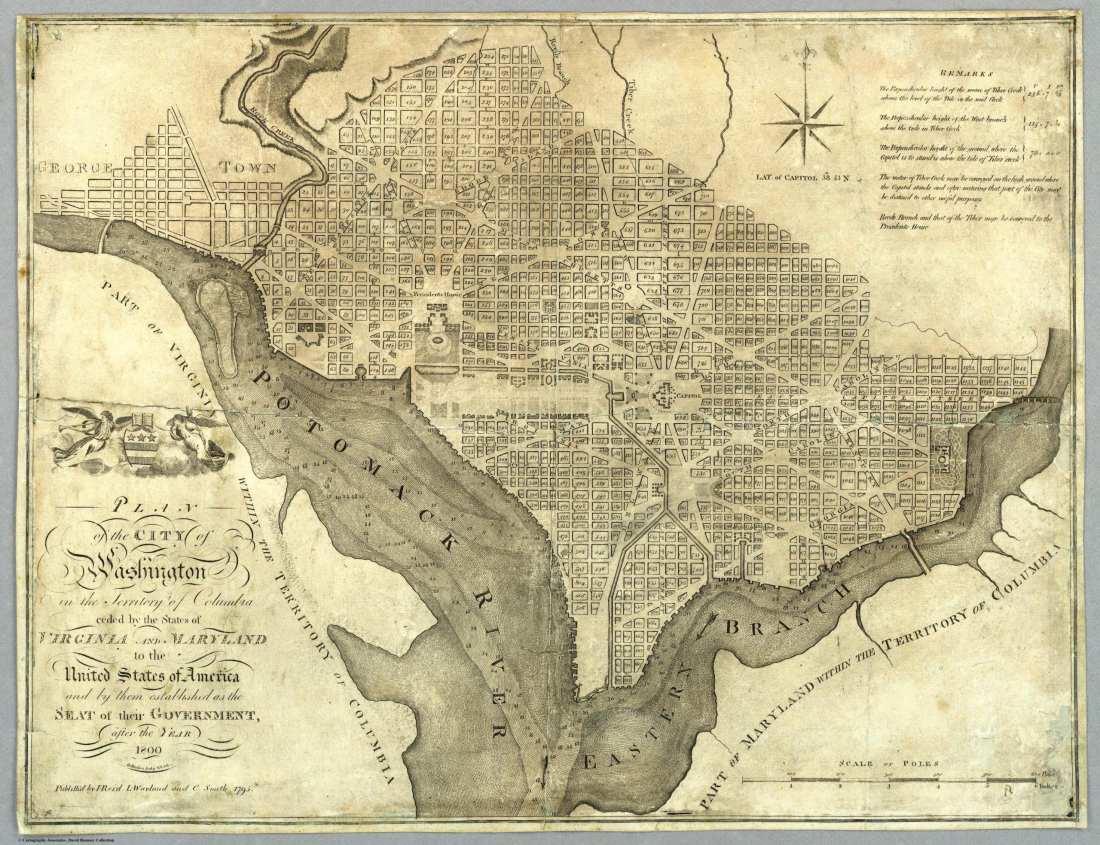

March 4, 1889, was a cold and rainy day in Washington, D.C. The newly elected Benjamin Harrison was due to be sworn in that day as the 23rd President of the United States. Harrison, a Republican, had been elected in an incredibly close and sometimes bitter election, defeating the Democratic incumbent, Grover Cleveland. In fact, Harrison had lost the popular vote the previous November, and he won the electoral college vote because he had narrowly won the state of New York despite Cleveland’s workings with the Tammany Hall political machine there.

No matter. Harrison was the man of the moment, and he felt the hand of destiny upon him. He was the grandson of a previous resident of the White House, one William Henry Harrison, known as “Old Tippecanoe” for his victories in wars against first nations more than half a century before. And he had been a senator from his adopted state of Indiana and served that state well in the US Senate. Also, Harrison had seen a great deal of action in the American Civil War, working with General William T. Sherman to split the Confederacy in half in the war’s last full year. So, all of that background led him to the inaugural day, and the rainstorm that beset the capital that day.

Interestingly, Harrison’s grandfather has the distinction of serving as president for only one month. It was during his ancestor’s inauguration during a winter storm that Old Tippecanoe had spoken for over an hour, and, as a result, he caught pneumonia that eventually led to his death and the rise of his Vice-President John Tyler to the office. Benjamin Harrison was well aware of his grandfather’s legacy, and his planned remarks were purposefully short. He wanted to touch on several key issues, however, in his speech. After such a contentious election, he felt that the occasion called for extending an olive branch to the Democrats and to the southern states that still stung from the defeat in the war that was still fresh in many minds down there.

In many ways, the election was a choice between personalities, as many elections are. Cleveland had raised some eyebrows during his term by marrying a young girl barely out of college for whom he had been appointed a guardian after her father had died. Harrison, on the other hand, was seen as a steady, solid, traditional candidate in sharp contrast to that type of “unseemly” behavior. Much muck had been thrown during the campaign over Cleveland’s unusual marital choice, and that had also caused some harsh feelings between the two campaigns.

But Harrison wanted to rise above all that electioneering. After the oath of office, and as he stood to read his prepared speech in the pouring rain, it quickly became obvious that there was no way Harrison could read what was quickly becoming a smeary sheaf of papers in his hand. It was then that a man emerged from the crowd on the platform behind Harrison, a man who quickly stepped up and held his umbrella over the head of the new president and kept it there while he finished his inauguration address.

When Harrison finished, he looked up to see who the kind man was who had allowed himself to get soaked so that the new Chief Executive could read his remarks on that historic occasion.

Harrison smiled and nodded when he realized that the polite man who had held the umbrella was none other than Grover Cleveland.