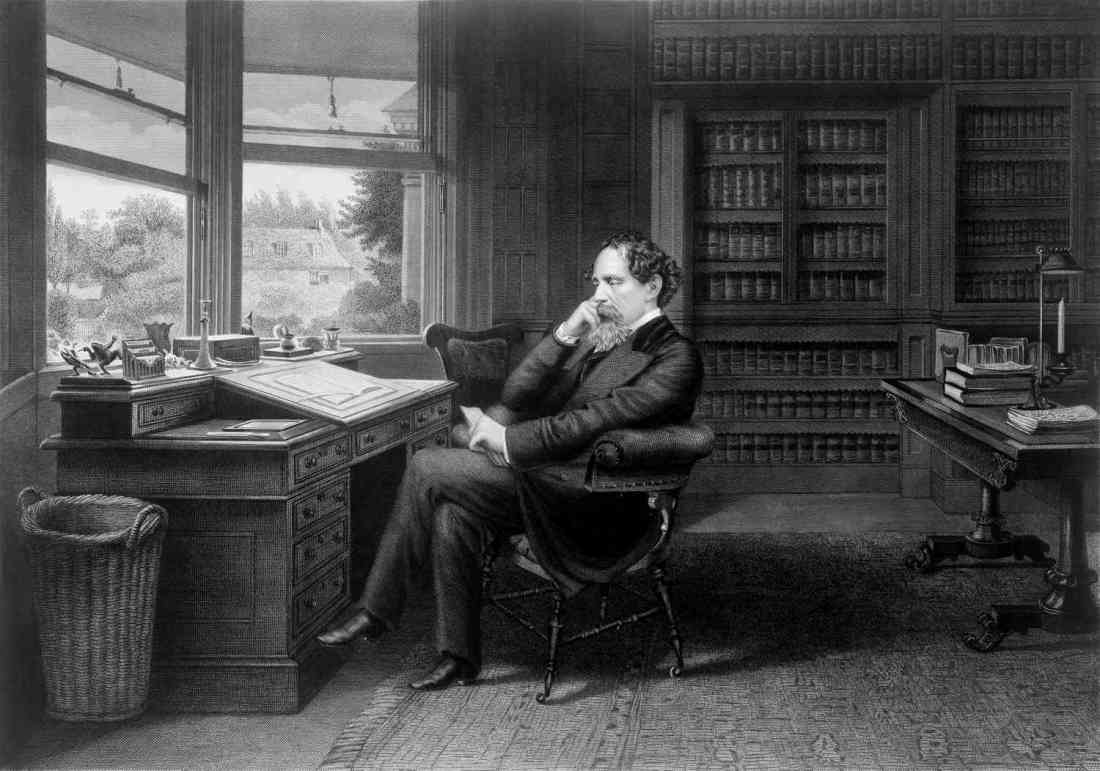

In 1847, a young would-be writer from Denmark visited London. On this trip, he had the fortune to meet the famous British author, Charles Dickens. At the time the two men met, Dickens was already a celebrated author, known for his stories such as Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickelby, and A Christmas Carol.

Dickens thought the angular young Dane to be eccentric but interesting. After their brief meeting, the young man wrote in his diary, “I was so happy to see and speak to England’s now greatest living writer, whom I love the most.” And, when he returned to his native Denmark at the end of his trip, he wrote a letter to his new acquaintance. “Dear Mr. Dickens,” the letter began, “the next time I am in London, I would wish to come spend some time with you if you would agree.“ Dickens wrote a short note back, acknowledging receipt of the letter and said that yes, sometime in the future, a visit from the young man would be welcome. It seems that Dickens answered more out of a formality and courtesy rather than truly extending an invitation.

Much to Dickens’ surprise, the young man showed up, unannounced, at his house…in 1857. And he brought with him enough luggage to stay for an extended visit. Unfortunately, the guest’s arrival could not have come at a worse time for Dickens. The celebrated author was in the middle of working on a play in London, and his marriage was going through a difficult phase. Nevertheless, Dickens and his family did the best they could to make the odd, thin Dane feel welcome in their home.

Immediately that were problems. It turned out that he did not have a good grasp of English. Dickens noted that his French was even worse. But the language difficulty was the least of the issues. He had a habit of sleeping until almost noon every day. When he finally woke up and came downstairs, he seemed flummoxed that breakfast, which had been cleared away hours before, was not made available to him. He would take long walks in the woods and fields surrounding the Dickens house. When he was with the family, he would get a pair of scissors and made elaborate and oddly strange cut outs from any paper he could find. These amused Dickens’s children at first, but soon they grew tired of the game.

The most bizarre part of the stay was when he requested that Dickens’s oldest son, for whom the young man seems to have grown inordinately fond, be made to shave him every morning. This was something that Dickens would absolutely not allow. Thus, the young man was visibly upset that he was now forced to go into town to be shaved by a barber. Soon, he would spend most of his time in town, shopping or walking the streets. The entire household was soon in an uproar. Everyone in the family and even the servants devised elaborate plans to avoid having to interact with him.

How do you tell an unwelcome houseguest that he has overstayed his welcome? Dickens found a way, and, after five long weeks, the visitor from Denmark left the Dickens household. After he arrived back in Denmark, the man wrote to Dickens and offered an apology and asked Dickens’s forgiveness for any breach of etiquette. Even though he never completely understood why he’d been asked to leave, he must have realized the tumult he brought to the household, and he tried to repair the damage done to the relationship. Dickens didn’t reply. The two never saw or spoke to each other again. And, shortly after the Dane had vacated the household, Charles Dickens pinned a note to the door of bedroom the unwelcomed houseguest had used.

The note said, “Hans Christian Andersen slept in this room for five weeks, but, to the household, it seemed like an eternity.“