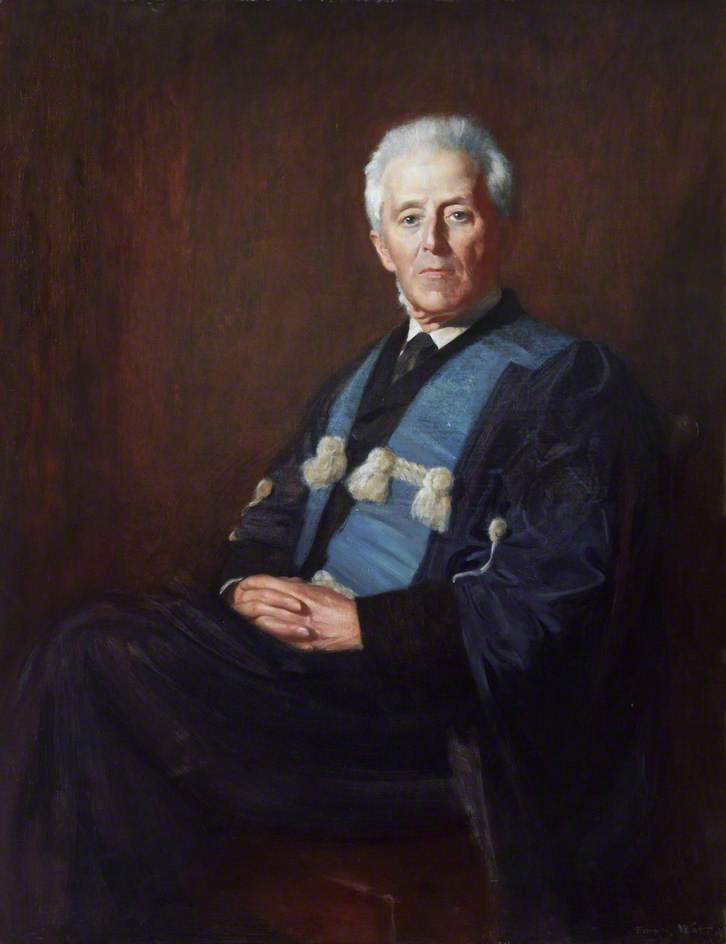

Joseph Bell comes to us as another of those people we know about but don’t readily know who he is specifically. Bell was a Scottish physician who was most active in the late 1800s in and around Edinburgh. His reputation and ability was such that, when Queen Victoria visited Scotland (which was often since she loved it so), Bell acted as her personal doctor there. For most of his career, however, Bell was a lecturer and mentor at the University of Edinburgh’s school of medicine.

Born in 1837, Bell grew up in a family of doctors at a time when the medical profession was undergoing radical changes. The old, traditional, and often-unscientific and unhygienic medical methods were being discarded in favor of scientific theories and cleaner, safer, practices. And the University of Edinburgh was on the forefront of this new, better, and more scientific approach to the practice of medicine. For example, the school pioneered such advances as the use of chloroform in surgery (Dr. James Simpson) as well as the adoption of antiseptics in medicine (Dr. Joseph Lister–the creator of Listerine).

Bell attended Edinburgh’s medical school and quickly earned a reputation as a thorough, keen observer of a patient’s symptoms. He was one of the first to consider a patient’s lifestyle and personal history as being a key to unlocking the secrets of a diagnosis, looking into the person’s background to help determine what the cause of a particular ailment might be. He receives credit for employing medicine in the solution of crimes, something we call forensic pathology today. A corpse, he said, could tell an keen investigator as much if not more than a living person can. In fact, the Edinburgh Police Force consulted with Bell on several important cases over the years.

One of Bell’s favorite things to do was to attempt to “read” a person simply by observing them. He would take students to the streets of the Scottish capital and point out passersby. For example, Bell might point out one person and tell his students that the man who had walked past them had recently come from China, or that the woman crossing the street towards them was the wife of a sailor. The students would then chase down the person and ask them if Bell’s instant diagnosis were correct. And the students found that Bell was almost perfect in those little exercises. The key, he said, was to be aware of the little things. The man who Bell had said had come fresh from China had a new tattoo on his hand that one could only get in Shanghai, for example. Bell even had the ability to tell a person’s occupation simply by looking at a person’s hands.

Such a teacher who was an astute observer of people and the little tells that could help a doctor in a diagnosis was certain to leave an impression on his students. One such student who was lucky to win a position as an assistant to Bell at the university went on to immortalize some of Bell’s characteristics in a series of stories in popular magazines of the time. In fact, a fictional character this student created, based in part on Bell, is one of literature’s most notable.

Of course, the student who admired and was inspired by Dr. Joseph Bell was Arthur Conan Doyle, and his character is the immortal detective, Sherlock Holmes.