Walter Hunt is one of the greatest inventive minds produced by the 19th Century in the United States. Remember that the same century produced Thomas Edison, Eli Whitney, Cyrus McCormick, and other creative geniuses who changed society as the world knew it. And I’m arguing that Walter Hunt holds his place among those giants of ingenuity.

That’s what makes the fact that you don’t know him or recognize his name so frustrating to some industrial historians. This mystery inventor was born one of 13 siblings in rural New York State at the close of the 18th Century, and he learned as much as he could at the local one-room schoolhouse. Eventually, he went to what we today would call an A&M college and received a degree in masonry. He liked tinkering in his barn. It was while he traveled to New York City in search of financing for some of his ideas that he conceived of his first important invention. He witnessed a street car accident in which a young girl was struck and killed. Walter then developed one of the first warning bells on streetcars to warn pedestrians of the approaching car. He sold his invention to the largest streetcar company in the county, and soon, his invention was used on streetcars everywhere.

And that story was repeated throughout Walter’s life. He would invent something and immediately sell it. As a result, he never really made the big money that other inventors did during that time. For example, Edison kept the rights to his creations and either became the manufacturer or licensed the rights to them to other industries. Thus, while we know about Walter’s inventions, we really don’t know about the man behind the inventions. His name was erased from his creations the moment he accepted (usually low amounts of) money for them. Instead, we know the companies that produced his inventions rather than their creator.

Home knife sharpener? Yep, that was Walter. Restaurant steam table? Ditto. The fountain pen? Well, Walter created the prototype of the ones we use even today. Rotary brush street sweeper? Better oil lamps? Paper shirt collar? Reusable bottle stopper? Prototype repeater rifle? An ice-breaker for ships? All of those and more came from the fertile imagination of Walter Hunt. And all of them sold for much, much less than they would make for the people or companies who purchased those inventions from him. However, he did manage to save enough money to open a machine shop in New York City in Greenwich Village. And it was there that he created one of his most valuable inventions.

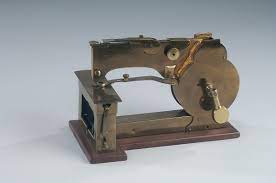

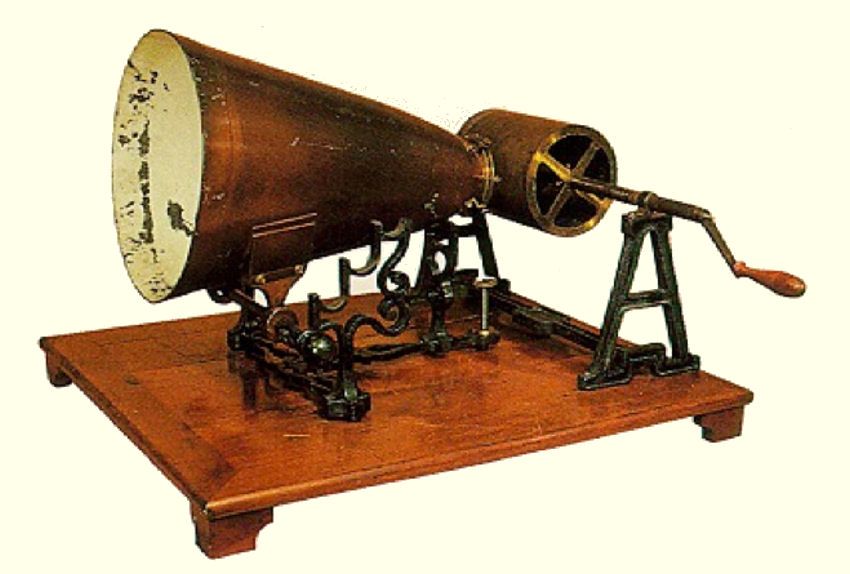

Up until that time, all sewing was performed by seamstresses in what amounted to sweat shops in the cities. Walter invented and built the first practical sewing machine, and it sewed faster than humans with the same accuracy and with even greater consistency of stitch. His wife and family were largely against his marketing or selling of this invention because of the number of seamstresses the machine would potentially render unemployed. Yet, he sold half interest in the machine to a man who promised to take the machine national but he…did absolutely nothing with it. Instead, the man changed the shape of the machine but left Walter’s stitching mechanism in place and pretended that he, not Walter, was the inventor of the apparatus. Later, a different man, Elias Howe, applied for the patent for the sewing machine. Walter began proceedings against Howe. The court found that while Walter’s machine predated Howe’s, Walter had failed to file proper patent paperwork and awarded the patent to Howe. Again, Walter didn’t gain wealth or recognition for something that he had created. Such was his luck. He died in 1859 of pneumonia, and almost no one noticed.

We still haven’t brought up the most significant invention by Walter. That one is, interestingly, both the most universal and the most simple of all of his creations. It was the one that would go on to make the most money world-wide. Of course, in typical Walter fashion, he sold the rights to it for the equivalent of $14,000 today. It was also one of the inventions he thought little of. Yet, if you know Walter at all, you know him for this. In fact, you probably have one or several of them in your house right now, thanks to Walter Hunt.

It’s the safety pin.