Ferdinand de Lesseps is a name you don’t recognize most likely, but you definitely know his work and his impact on the world. de Lesseps was a French diplomat and civil servant who led the French organization that built the Suez Canal in the 1800s. The canal was a modern phenomenon at the time since the desire for a connection by sea from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea is as old as history. Over the millennia, many civilizations tried but failed to cut a channel between Africa and Asia, and it was mostly the organizational work of de Lesseps that accomplished what no one else had been able to do. As a result, the man became a major hero to the French Republic and an international celebrity.

Thus, it made perfect sense for him to be the one to lead the next effort to build an important canal, this time across Central America. Such a canal would connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. If built, the channel would save over 8,000 miles of sea travel by saving ship traffic from having to go all the way around the tip of South America to get to the other side. The potential savings of time and money were astronomical. All that de Lesseps had to do was to carve a ditch of about 50 miles across one of the most narrow points in Central America, across the isthmus of Panama.

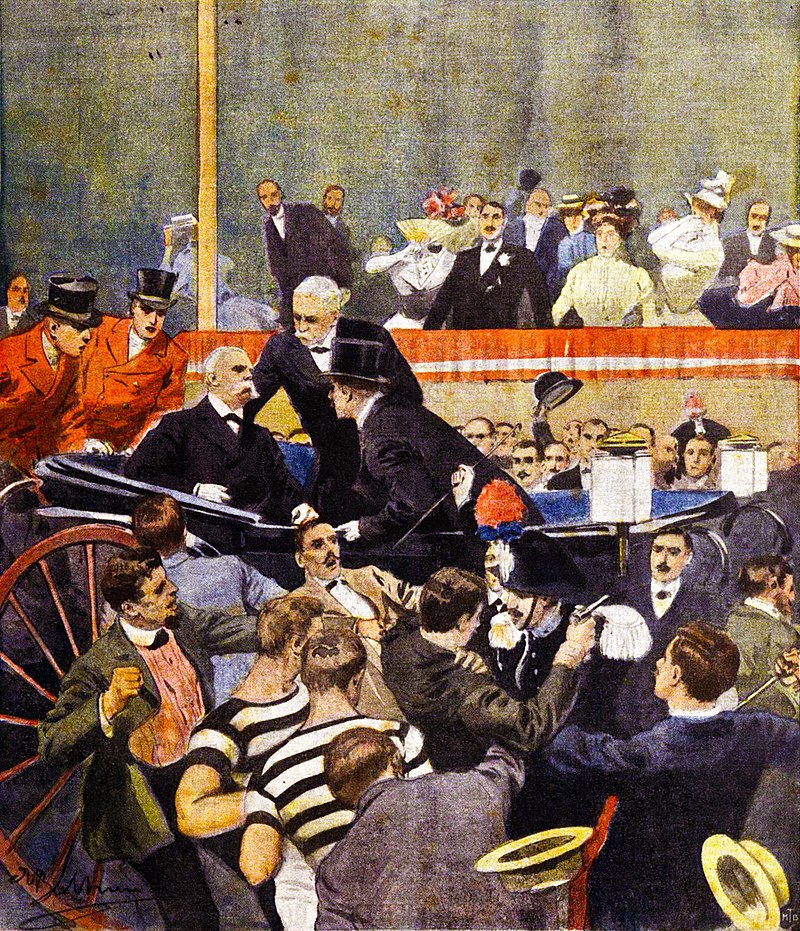

It was with great fanfare, therefore, that the great canal builder de Lesseps was on hand in Panama to be the one to turn the first shovel of dirt, symbolizing the start of work on the project when construction began. But conditions in building the canal in Panama were remarkably different than those in the Suez. To start with, the construction was met with what seemed like insurmountable difficulties. Their equipment was good and modern, but it was mostly too small to do the task. One excavator said it was like digging a well with a teaspoon. The equipment would have been fine for the sands of the Suez, but, faced with the rock and mud of the Panamanian jungle, the machines bogged down quickly. There were landslides because of the rainy season when water poured down the hillsides of the construction sites. And when it wasn’t raining, it was scorchingly hot.

And then there were the tropical diseases, specifically the twin evils of yellow fever and malaria. Remember that this was in the late 1800s, in the period before vaccines and any types of proper treatment of scourges. Yet, despite these impediments and setbacks, the effort eventually removed more than 75 million cubic yards of dirt and rock. de Lesseps visited the construction sites and encouraged the workers that they were making good progress and that their efforts would be remembered forever in history.

de Lesseps local guide and on-site project manager was a man named Philippe Bunau-Varilla. Bunau-Varilla would become the most important Panamanian involved in building the canal. He was the one who organized the local workers and made all the arrangements for the logistical necessities like food, shelter, and facilities. And he was the mediator between the local/federal authorities in Columbia (who owned the land at the time )and the foreigners who were financing and overseeing the process of building the canal. Importantly, and unlike de Lesseps, Bunau-Varilla was an engineer. He disagreed with de Lesseps’s concept of making the canal a sea-level project rather than using locks. He understood that locks meant more cost but, ultimately, a much more simple process and a faster construction time.

By 1902, the work done by de Lesseps had produced the basic framework and route for the canal. However, because of the sicknesses of the location as well as construction accidents, over 20,000 workers had lost their lives in the effort. Investment money had dried up. Interest had waned in the work. It needed fresh eyes and a new perspective. And, by then, the aged Ferdinand de Lesseps had died. An offer from another investor came in, an offer to purchase all the equipment and the rights to complete the project. After almost no deliberation, the organization accepted the offer and sold out. This new investor then completed the canal in short order, using Bunau-Varilla’s idea for locks.

And who was that new investor?

Of course, it was President Teddy Roosevelt and the United States Treasury Department.