We’ve spoken before about how some historians argue that the modern world largely began in the period between 1820 and 1850. The use of steam engines to power factories, the creation of the railroad, and the invention of the telegraph occurred during those thirty years. It can be argued that almost all modern conveniences are merely modifications or improvements over these technologies. For example, the telephone is simply a better and more convenient telegraph, cars are trains for individuals that don’t run on tracks, and so on. Few inventions had an impact on society as the telephone, however.

We are all familiar with the story of how Scottish inventor, Alexander Graham Bell, and his assistant, Thomas Watson, were working on their telephone device one day when the first phone message was transmitted. The story goes that one day in 1875, Bell had spilled something toxic and needed Watson’s help, so he said something like, “Mr. Watson, come here–I need you,” and Watson heard the message through the machine as he was in the next room. Soon, the nation’s cities were crisscrossed with telephone wires tying people together instantly.

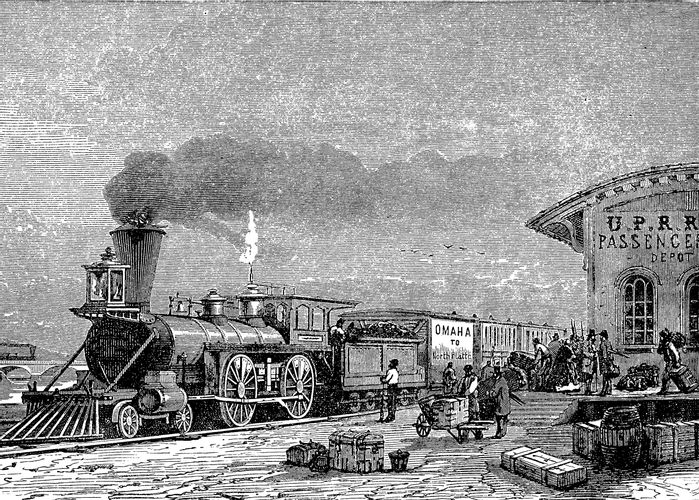

But there was no transcontinental phone system in place. The railroad had connected east to west in 1869. Paved highways from one ocean to the other were finished by 1913. It would be another two years later when phone wires were finally hung across the United States so that a phone call could be placed in New York and received in San Francisco. And to mark that historic milestone, a celebration and many commemorative events were planned. Now, phone lines had been connected from New York City to Chicago by 1892; that network had been expanded to Denver by 1911. And the final section across the Rocky Mountains to California was finished by late 1914. The president of American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T) at the time, Theodore Vail, had tested the system that year, and it worked, but that first call was kept secret so that the event could be properly celebrated and marked. That’s why the first “official” call was scheduled for January of 1915.

Several dignitaries were to be involved in the call. Vail would be listening in from his winter home in Georgia. The mayors of both New York and San Francisco were also listening in on the line. And President Woodrow Wilson himself later spoke live from the White House to an audience assembled in San Francisco. In his remarks, Wilson noted that it boggled the imagination that a voice from thousands of miles away could be heard almost instantly by the people there. He mentioned the thousands of workers over the years since the invention of the device, the mostly anonymous men and women who manned the operator stations, erected the telephone poles, buried or strung the wires, and did the maintenance on the lines that made all of that possible. That part rubbed Vail the wrong way a little, because he wanted the celebration to recognize the power of AT&T and not the “little people” who were involved.

But the first call that day in January was placed from New York. Telephones had come a long way since Bell had first spoken to Watson 40 years earlier. To honor that event, the first official intercontinental telephone call repeated the words that Bell had said, too: “Mr. Watson, come here. I need you.” And, to make the call even more memorable, those words were spoken by the inventor himself, Alexander Graham Bell, on that January day in 1915.

And, on the other end of the line in San Francisco, when he clearly heard the same message that Bell had said to him 40 years earlier, Thomas Watson smiled.