Chris had developed the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis in the late 1970s, and by 1983, the issue forced him out of the operating room. That was a blow. He had been a surgeon for all his adult life, specifically a heart surgeon. It was all he wanted to be ever since he was a child. Born in South Africa to a father who was a minister in the Dutch Reformed Church, Chris had been taught service to others from an infant. One of his siblings, Adam, had been a “blue baby,” that is, a heart defect caused his skin to appear blue because of a lack of oxygenation in the blood. That had a big impact on Chris’s decision to become a heart surgeon.

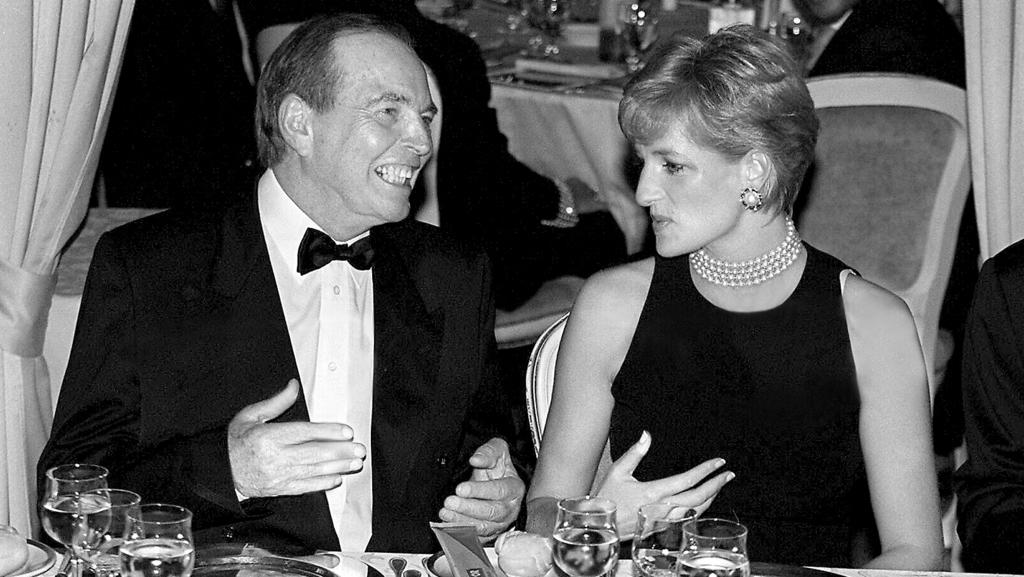

After his education and residency in South Africa, Chris grew interested in correcting intestinal underdevelopment in newborns, specifically a bowel obstruction that was often life-threatening. Through research and experimentation, Chris developed a new protocol and surgical procedure for fixing the issue so that what had been a potential deadly situation became a fairly common and routine surgical fix. But his true love was cardiological surgery. And he was great at it, developing new techniques and becoming well known in that corner of the medical establishment. And Chris was a heartbreaker. The handsome surgeon had girlfriend after girlfriend, managed to marry and divorce three times, and had six children over the course of his life. He dated models, actresses, and even hobnobbed with royalty. For Chris, the women were part of the successful heart surgeon career.

But, then, because of the arthritis, by 1983, that well-established career was over. What would he do? Chris then experienced something of a mid-life crisis. He was in his early 40s, at what should have been the prime of his career as a surgeon. Chris turned to anti-aging research. While his hands had betrayed him, his mind was as sharp as ever. But Chris, for reasons unknown, put his considerable reputation behind a questionable skin cream, a product named Glycol. Chris said that research (it wasn’t clear if it was his research or someone else’s) showed the product reversed wrinkles, hydrated the skin, and could visibly reverse the signs of aging on the face. Well, truth be told, pretty much any cream will do hydrate the skin, including Vaseline, according to a article published at the time. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration didn’t offer Glycol approval for use as a treatment for aging because, they said, the claims were hokum. Rather than a drug to stop aging, Glycol was classified merely as a cosmetic. Chris was heartbroken. He retreated into himself and stopped all work on the anti-aging idea.

What do you do when your career is over and your reputation is in tatters?

Chris didn’t quit. He worked doubly hard to re-establish his reputation. With funds from his years as a surgeon, Chris established a foundation, based in Austria. The foundation is still ongoing. It provide funds for the families of low-income children from developing nations who need live-saving heart surgeries to travel to Europe where they could have needed surgeries they ordinarily couldn’t afford. Through his foundation, Chris continues to help provide for these surgeries even though he passed away in 2001 at the age of 78.

It turns out that the heartbreaking surgeon salvaged his reputation by opening his heart in providing for others and making miracles happen for families who faced the possible loss of their loved ones. But that had been his life as a surgeon as well. You see, before arthritis took his surgical abilities away, Dr. Christiaan Barnard had been the first surgeon to successfully transplant a heart from one human to another in 1968.