In 2016, Time magazine published a story that recognized the 75th anniversary of the entry of the United States into World War 2. It did so by recalling the stories of several children whose lives were directly affected by that war, children who witnessed the war first-hand, and children who, as adults, were still alive and sharing those tales when the article was written. And the stories these adults told of their experiences in wartime still resonate today, now more than 80 years after the US entered the war.

Take the story of Walter, a boy who was 13 when he witnessed the power of modern warfare first-hand. Walter tells of feeling an explosion of bombs so close to him that it almost knocked him down, even though he was almost half a mile away from the blast. He then recalled how, later that day, the long procession of coffins, each one containing the body of one of the dead in them, the dead who had been the targets of the bombing, were brought past his house. And he clearly remembers the blood splotches that were clearly evident on and stood out against the yellow-white of the coffin wood as they passed, stacked high on the back of military trucks.

Then there’s the tale told by Edwin who was 14. He was eating his cornflakes one morning when he saw the planes fly low overhead and then begin to strafe the targets on the ground below them. He was fascinated and horrified at the same time. It seemed like a movie to Edwin; surely, humans couldn’t willfully bring such violent destruction to other humans in this way, he remembers thinking at the time. He then remembers the countless nights of blackouts, of building a bomb shelter, of hoping–no, praying–that if he hid under his bed when and if the planes returned, that the mattress would be thick enough to stop the bullets…

How about the tale told by a boy whose family called “Chick?” Chick was 12 when the war came home to him. He and his brother were making some spare change at a local cafe by washing dishes for the breakfast customers. A taxi driver stopped by for coffee and told the boys through the service window to the back that if they wished to see the war first-hand, to go outside and climb up on the roof of the cafe. That vantage point would give them a great view of some live war action. The boys did so. But what Chick saw frightened. him: Hundreds, he later said, hundreds of puffs of smoke indicating bombings and anti-aircraft fire. He took his brother and ran home. He yelled for his mother as the brothers entered the yard in front of their home. “Momma! It’s war!” he screamed. Sure enough, as soon as his mother ran out of the house at her son’s cry, a bomb screeched down and struck the neighbor’s house with an ear-splitting explosion. Chick knew the family next door was dead. The fire that resulted from the bombing quickly spread to all the houses in the neighborhood, including that of Chick’s family.

All three of these boys and many, many other children saw war up close and personal, witnessed death up close and personal. Today, in dozens of conflicts around the world, children are still forever changed by their personal experiences with warfare and the death and destruction that are caused by it. These American boys who spoke to Time 75 years after the fact, however, were slightly different than other American children during World War 2.

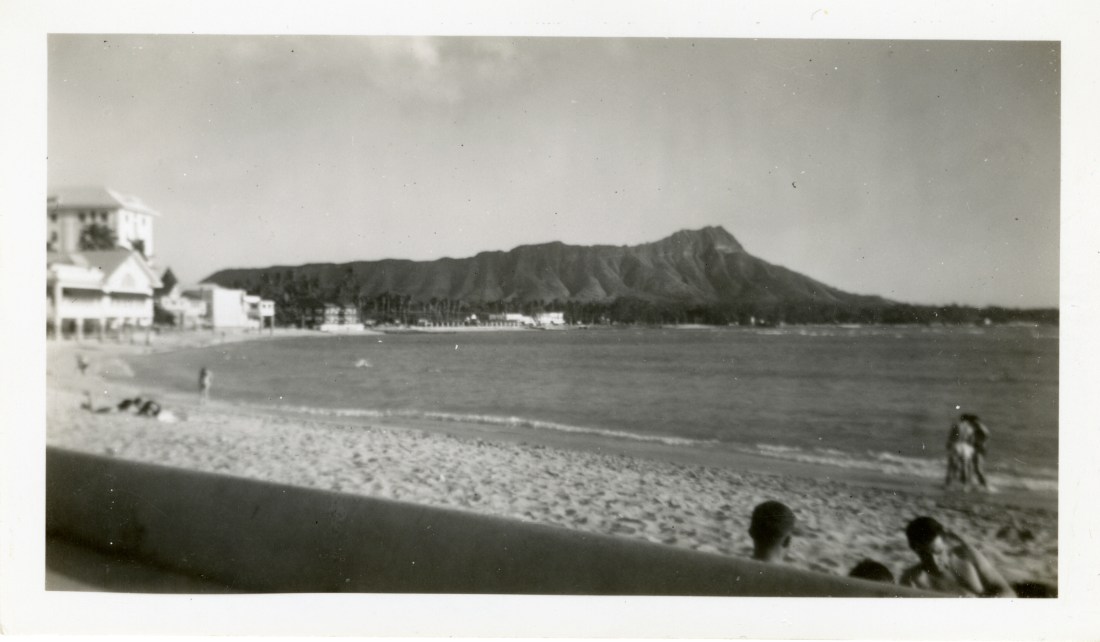

You see, all three of these boys were of Japanese descent and living in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, when the Japanese Navy launched their attack on Sunday morning, December 7, 1941.