Some people dearly love crossword puzzles. Before newspapers became passe, most daily papers featured a crossword puzzle for their readers. The British seemed particularly keen on this past time. One of the most famous daily crosswords was featured in the London Daily Telegraph paper. Published since 1855, the Daily Telegraph is, in some circles, the newspaper or record in the British capital city.

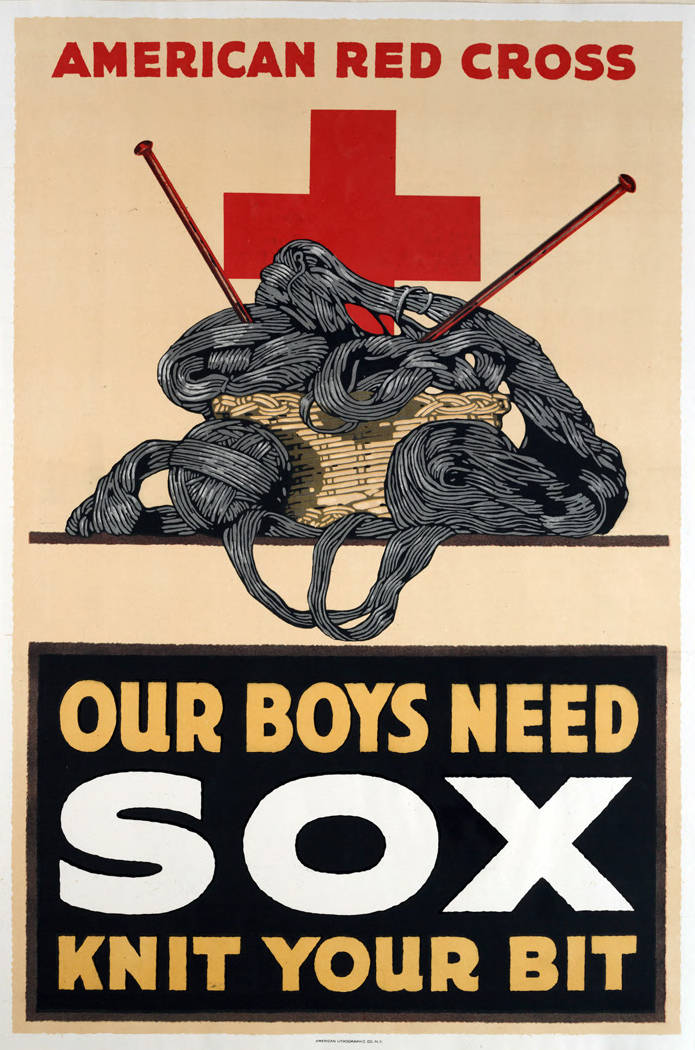

During World War 2 in Britain, with the nation under siege from the Nazi’s blitz bombings and suffering from various rationing and shortages, things like the daily crossword provided many citizens with a welcome respite from the issues of wartime. Like many newspapers, the Daily Telegraph received their puzzles from people outside their direct employ. One of the paper’s daily crossword compilers was a school headmaster named Leonard Dawe. Dawe had led an interesting life before his teaching career. He’d played football (soccer) for England in international matches, even being selected to be a part of the national team at the Stockholm Olympics in 1912. During World War 1, Dawe saw deployment to the Middle East, and he came out of the war with the rank of Major in the army.

But World War 2 saw Dawe serving his nation by forming young minds in the Strand School. The school for boys had been removed to the countryside in order to protect the youngsters from the German bombing of the city. There, the boys and their teachers enjoyed the countryside and the relative quiet found there. Not too far away was a military camp for British and Canadian servicemen, and that place proved to be a source of adventure for the schoolboys as you could imagine.

Dawe submitted his crosswords to the Daily Telegraph and invited his students to help him put those puzzles together for the paper. The boys were delighted to help. Dawe’s habit was to leave a blank puzzle template in his office, and he asked the boys to come in freely and fill in the blanks with words. Dawe would then complete the puzzle by creating the clues that matched the words the boys provided. The collaboration proved fruitful, and Dawe never failed to send good puzzles to the paper.

But, then, in the spring of 1944, military intelligence showed up at Professor Dawe’s door. He was arrested for suspicion of espionage. Everyone was shocked. Why, they wondered, would a distinguished schoolmaster (and a veteran, at that) risk his reputation and career by being a spy? It turned out that some of the words that appeared in Dawe’s puzzles that spring were important to the war effort at the time: Utah. Sword. Overlord. Mulberry. Gold. Omaha. Neptune.

Dawes sputtered his innocence when put under intense interrogation. He couldn’t think of how those words could have come into his puzzles. Then it hit him. The boys were going to the nearby basecamp. They must’ve been overhearing these words from the soldiers there and coming into his office and putting the words on the template. You see, those words were codewords for what was about to be the Normandy Invasion–D-Day–scheduled for June 6, 1944.

And Dawe’s schoolboys almost gave away the Allies greatest secret.