Having been in Europe for a handful of years in my life (a couple in Eastern Europe and a couple in the western parts), I can testify to the idea that many Europeans look at the United States the way a father would look at a 12 year old who has been handed the keys to an 18-wheeler. They are (probably rightfully) convinced that the task of driving the world is beyond our ken. And, until the inevitable crash occurs, they watch our efforts with a mixture of bemused horror. The same can be said for what Americans call “culture.” As in Europeans (especially the French) feel that we have none. That also applies to our food preparation and consumption in the States. The famous American food author, M.F.K. Fisher, was asked once by a French chef how she could write about American cuisine when such a thing didn’t exist. The idea is that we in America have no tastes or refinement. And, given the behavior of many from “across the pond,” they aren’t far off.

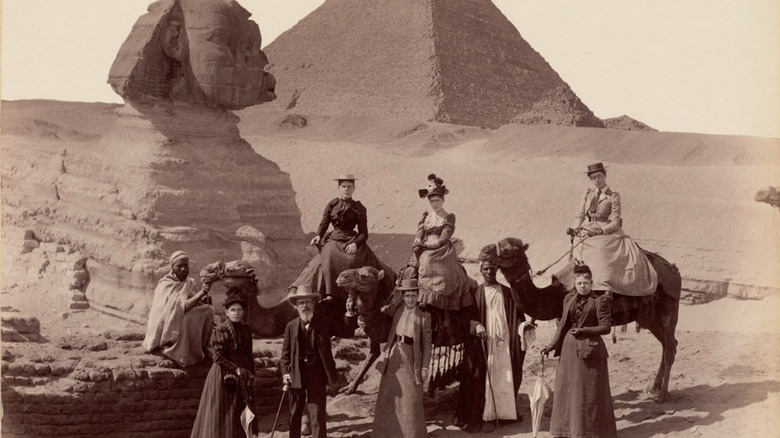

Take the case of an American tourist on a tour of Europe in the late 1860s. That used to be a “thing” where Americans would take a trip to Europe (usually referred to as The Grand Tour) to soak up the culture and experiences of the Old World as a way of expanding one’s horizons and broadening one’s mind. On a trek that covered over 20,000 miles (32,000 km), this particular American saw some amazing things. Besides hitting all the famous European capital cities, he also traveled extensively in the rural areas as well.

By boat, train, carriage, barge, and horse, this traveler went from England to the Holy Land and almost everywhere in between. And while he recorded what he experienced (things like the Parisian Exhibition of 1867 and an exclusive tour of the Vatican), he was more impressed by how small everything was. The Holy Land, for example, disappointed him. “This whole place could fit inside one or two counties back home,” he lamented. The history, architecture, and scenery bored him. And when it didn’t bore him, it confused him. Why did the Germans keep old buildings when more modern ones would be warmer, safer, and larger, he wondered. Things were too close together. People were rude. Shopkeepers kept trying to make him pay more because he was a tourist. Unsurprisingly, it wasn’t too far into the journey that he really began to miss home.

But, more than anything else, it was the food on his trip that made this American homesick. And it wasn’t that there wasn’t enough food on the trip; in fact, there might have been too much. No, his complaint was that the food was mind-numbingly and palate-boringly, well, boring. The food of Europe, he noted, was “fair to middling.” He really missed his native land’s delicacies. We would say this tourist wanted his “comfort food” in the worst way. And, so, in an effort to pass the time on what seemed like an interminable trip and to remind himself of the great repasts of his past, the tourist made a list of his favorite American dishes.

And what a list! Again, for someone who was writing in the 1860s, I can attest that many things on this long, long list of American comfort foods are also among those that I miss as well. Being someone from the south like him, please let me say that I can relate:

- Fried oysters

- Southern fried chicken

- Southern hot biscuits

- Hot pancakes

- Thanksgiving dinner, including turkey and cranberry sauce

- Apple pie, cobblers, and other baked desserts

- Ice in drinks, especially ice water

You get the idea. The list ran on and on and included other regional specialties peculiar to the US. Finally, the Grand Tour finally ended several months later, and the homesick American came back home to the country and gastronomy he loved and missed so much. He wrote a book about the trip, and the book became the one book that sold more copies than anything else he wrote during his lifetime. The book is The Innocents Abroad. And the American tourist who missed his nation’s food?

Mark Twain.