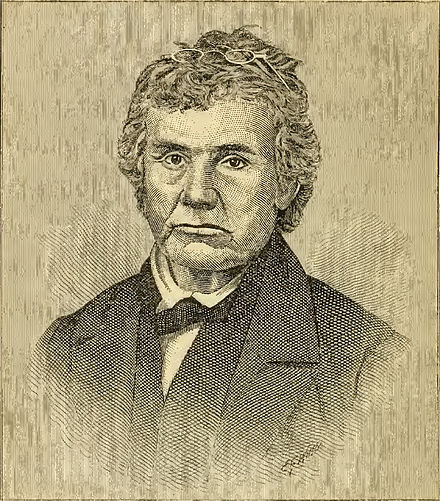

Peter Cartwright was a minister on the frontier of the United States in the early 1800s. Born in Virginia at the end of the 1700s, Cartwright became an ordained member of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1801 and moved west to help bring the frontier settlers to Christianity. The frontier at the time was where many poorer people moved, people who were less likely to be “churched” and familiar with biblical principles. Cartwright felt a strong calling to go preach on the edge of civilization (Kentucky, at the time) and work among these settlers. Thus, he was part of what historians call the Second Great Awakening, a time of religious revival in that part of the western settlers of the United States.

There was a major issue that Reverend Cartwright found in Kentucky, however. At that time, human slavery was still legal since this was the time before the American Civil War. And Cartwright found that he could not tolerate his parishioners owning other human beings. After several years in Kentucky where he married and had some children, he decided to move to a northern state where the practice of slavery was illegal. Thus, he and his family made the trip to Illinois.

Cartwright was part of that generation that came along as the Revolutionary War generation was dying out. He and his contemporaries felt a strong emotion of patriotism, and they began to think of the Founding Fathers as being practically ordained by God to have started the most Christian, the most holy, the most God-blessed nation on earth (a feeling that is shared today by many as well). He became a chaplain in the US Army during the War of 1812 and saw it as he duty as a citizen to run for office and serve his fellow Americans politically. And so, the frontier pastor became a politician as well.

He was a rare person for the day, however. As a Jacksonian Democrat, he was nonetheless an abolitionist. In Illinois, his popularity as a minister and his advocacy of the elimination of slavery saw him elected to the Illinois State Legislature in 1830 and 1832. He ran for governor once, but he was defeated. Meanwhile, he kept preaching on the frontier, bringing many people to Methodism over the years and the miles. Cartwright was instrumental in setting up several Methodist colleges in Illinois as well, and he served the state Methodist Convention for decades.

Then, the chance came in 1846 for him to run as a US Representative from Illinois. His opponent was a member of the Whig Party and a man who had little political experience. At first look, it would seem that Cartwright would win the election easily against a young and inexperienced Whig, but many people in the state began to tire of the pastor’s mixing of politics and religion. Also, while many people were becoming converted to Methodism, many others continued to enjoy such things as alcohol, specifically hard cider that was made from the many apple trees planted across the state a few years before by one Johnny Appleseed, no less. Cartwright’s insistence on abstinence from alcohol and his calls for laws prohibiting the making and selling of alcohol ultimately changed the election against him. He lost a close election, and that loss made him decide to never run for public office again.

And that’s interesting, because the Whig candidate who did win that election decided to make it his life’s work–next to the study of the law.

That young Whig and new Illinois representative was Abraham Lincoln.