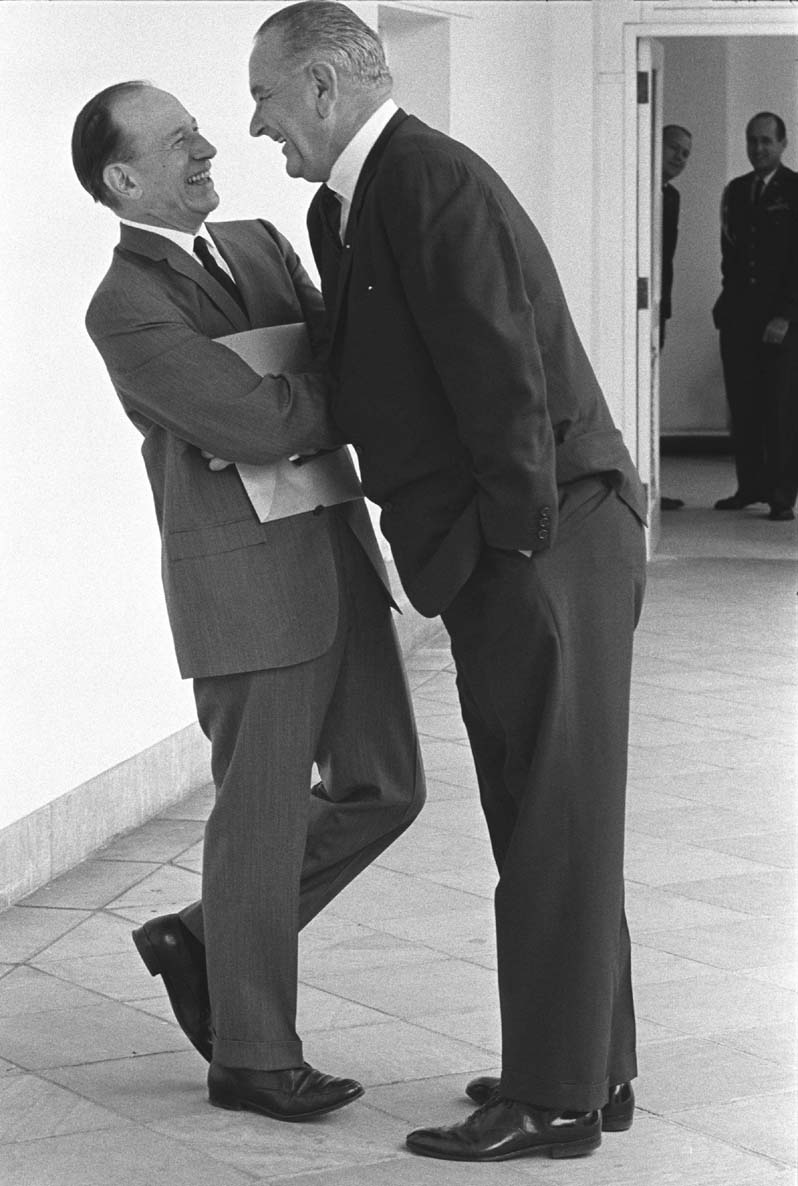

Lyndon B. Johnson was the consummate politician. As a congressman, senator, and, eventually, president, LBJ would lie, cheat, steal, bully, and threaten to get his way when it came to passing legislation. And it was not only that he could force people to do things for his agenda, but part of his power lay in his charm and charisma. Johnson towered over most people, being well over 6’4″ (1.9m) and was the consummate storyteller and mimic; he would often imitate colleagues, friends, and enemies, skewering them with dead-on impressions. And, as part of that larger-than-life persona, Johnson would often overstate his role in affairs to make himself seem more important to events that he actually was.

Take the instance of a story Johnson would often tell of how close of an advisor he had been to President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the years leading up to World War 2. Now, while Johnson was a young congressman from Texas and he did have opportunity to meet with FDR in the White House from time to time, in no way did Roosevelt consider the tall, thin Texan to be a trusted confidant. But that’s not the way LBJ would tell it in later years.

It was in January 1953, in the dining room of the US Senate in the Capitol Building when Johnson, at the time the second-most powerful man in the senate, came into the room. As was his custom, he would make his way around the room, shaking hands and trading bon mots with the other senators and their staffs. When he came to the table of the powerful senator from Wisconsin, Senator Joseph McCarthy, the senator and the staff at the table rose to shake Johnson’s hand out of respect. That is, except for one lower-level staffer from McCarthy’s office. This young man stayed seated and glowered at the powerful Johnson.

As Johnson made his way around the table, he reached the seat of the young man with the scowl on his face. Johnson knew that the staffer was purposefully being rude. You see, LBJ made it his job to know everything about, well, everybody. He knew why the young man refused to stand and shake his hand. So, in a show of power and to put the young staffer in his place, Johnson hovered over the seated man and stuck out his hand. Onlookers later said that the staffer swallowed hard, looked around the table at the other, standing staffers, and slowly stood up and offered a limp hand that Johnson took and shook vigorously. His point made, Johnson then made his way to the next table. The young staffer slank back into his chair and finished his lunch.

Later, an aide to Johnson asked him about the incident. Johnson let out a loud guffaw. He then reminded the aide of the following story, and it was a story that he LBJ had told often before. He said that McCarthy’s staffer was the son of a government appointee back during Roosevelt’s second term. During one of their meetings in the White House, Johnson said that FDR had complained about this staffer’s father. And Johnson bragged that he had advised Roosevelt to fire the man because he was a Nazi sympathizer and was antisemitic. To hear LBJ tell the story almost two decades later, it was Johnson’s advice that convinced President Roosevelt to ask for the appointee’s resignation. The young staffer’s rudeness and dislike of Johnson therefore stemmed from LBJ’s part in getting his father fired.

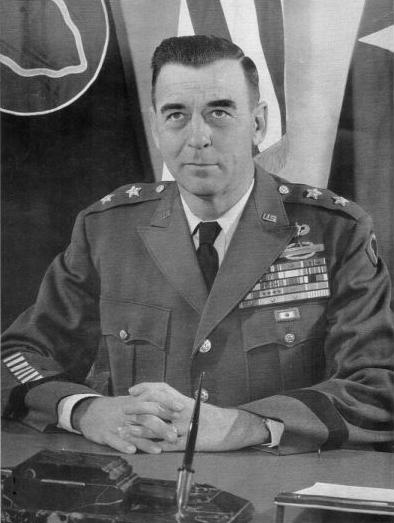

Of course, Johnson grossly overstated the importance of his advice to Roosevelt. The fact was that President Roosevelt had already made up his mind about removing the appointee from his post long before Johnson said anything–if in fact he had said anything at all to the president. So, while it probably wasn’t Johnson’s hand in getting his father removed from the post as much as it was that he had heard about the story Johnson told about the incident, the story about making himself out to be more important and influential than he was. You see, the young man, that scowling McCarthy staffer, he was the opposite of Lyndon Johnson. He was almost an anti-politician. He was more of a crusader, a fighter for justice and truth. To him, men like Lyndon Johnson were part of what was wrong with Washington. And the young staffer was working to bring honesty and accountability to congress. And to know that LBJ was telling untrue stories about his dad and laughing about his dad’s removal from his government appointment, well, it was all too much.

By the way, the post that the staffer’s father had held was the ambassadorship to the United Kingdom in the days before World War 2. He knew that his father wasn’t fired from the job and he also knew that Lyndon Johnson had nothing to do with his father’s resignation from the post.

And that’s why, in January 1953, young Bobby Kennedy refused to stand and shake Lyndon Johnson’s hand.