Hobo is one of those words of which we have no clear etymology. However, the word is in our vernacular and has been since the 19th Century. During the Great Depression in the United States, the roads and railways were clogged with young men (and a few women) who were traveling around looking for work, food, direction. With almost 25% unemployment, it’s no wonder why. My uncle Bubba (his name was Melville Carr Baker; that’s why everyone called him Bubba) told his tales of riding the rails in the 1930s from town to town.

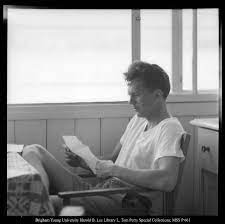

Another young man who did this was one Arnold Samuelson. From Scandinavian stock in the American Middle West, Arnold had finished his college work and was, like most men aged 22, uncertain about his future. That’s when he decided to stick his thumb out on the highway and travel the United States, to see what there was of the amazingly large nation. Eventually, Arnold found himself sitting on top of a boxcar as it made its way down the bridges from Miami into Key West, Florida, the southernmost point in the nation on the East Coast. When he arrived in Key West, it was almost summer, the time when people at that time left Florida to escape the heat and mosquitos.

That first night in Key West, Arnold slept on the dock; the sea breeze kept the bugs at bay. But the next night, a couple of local policemen said he couldn’t sleep in public and offered to put him in their holding cell for the night. One rule of being a hobo, at least according to Uncle Bubba, was that you never said “no” to the police. So, Arnold went with them. That started several days of walking around the town during the light and sleeping in the mosquito-filled jail cell at night.

On one of his walks about the town, Arnold found himself in front of a large, older, typical Key West house. He knocked on the door, and a burly, shirtless, mustachioed man came out and confronted him. Arnold stammered hello, and the man asked him, brusquely, “Waddaya want?” Arnold sketched out his tale to the man, and he could see that, the more he explained his situation, the more relaxed the man became. “So, you just want to chew the fat?” the man said with a smile. Arnold nodded. The man said that he was busy, to come back the next morning and they would sit on the porch of the man’s house and have a proper talk. Arnold agreed. That began several days of Arnold waking up in the jail, scratching his new bug bites, then coming to the man’s house and having deep, meaningful conversations about life, love, art, and Arnold’s favorite topic, writing. The man was quite knowledgeable about many topics and filled with good advice and helpful life-tips for the young hobo.

“If I wished to learn about writing and about life,” Arnold asked him one day, “what books should I read?” The man got up and got a piece of paper and a pencil. He made a list of books for Arnold to get and peruse. “Those’ll teach you about what you need to know,” he told Arnold. One day, the man gave Arnold the news that he had to take his boat up the coast. He asked Arnold to do him a favor. “Say,” he said, “would you want to come along? You can live on the boat and watch out for it when I’m not on it.” Arnold eagerly agreed. He couldn’t believe his good fortune. He ran back to the police station and grabbed his tattered bag, thanked the cops, and ran back to the man’s house. That was the beginning of a whole year of sailing on the Caribbean with the man and his fishing buddies and other assorted guests. The man paid him a dollar a day, and Arnold was deliriously happy.

Arnold never did become a famous writer, but he did publish an interesting book about his experience there.

It’s called, With Hemingway: A Year in Key West and Cuba.