To say that the field of medicine has exponentially advanced in the past decade is an understatement of epic proportions. Our knowledge of how our bodies work (and how and when they don’t) doubles every 80 days or so according to one source. That’s why it’s almost impossible to comprehend that, within the past 200 years, doctors often treated some sicknesses by bloodletting.

Bloodletting, in case you didn’t know, is the practice of removing not a small amount of blood from a sick person based on the idea that sicknesses were carried in the blood or that the removal of “bad blood” would aid a person’s recovery from an illness. Pints of blood were often removed from patients, almost always resulting in the afflicted person become more sick instead of getting better. Doctors of the day would usually employ a scalpel on a vein and then allow the blood to flow into a pan, large dish, or bowl. Sometimes, the doctors would use leeches placed all over the body of a patient, but this method was eventually discarded as being too slow to remove the “sick” blood from the affected person.

Part of the reason for the belief in bloodletting was that the human body contained four “humors:” Black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood. If one of these four got to be out of balance compared to the others, the belief was that this imbalance would result in sickness. Since there was more blood than these other “humors,” then it was thought that the offending humor was most often blood. Oh, and don’t look now, but the practice is still occurring in some cultures.

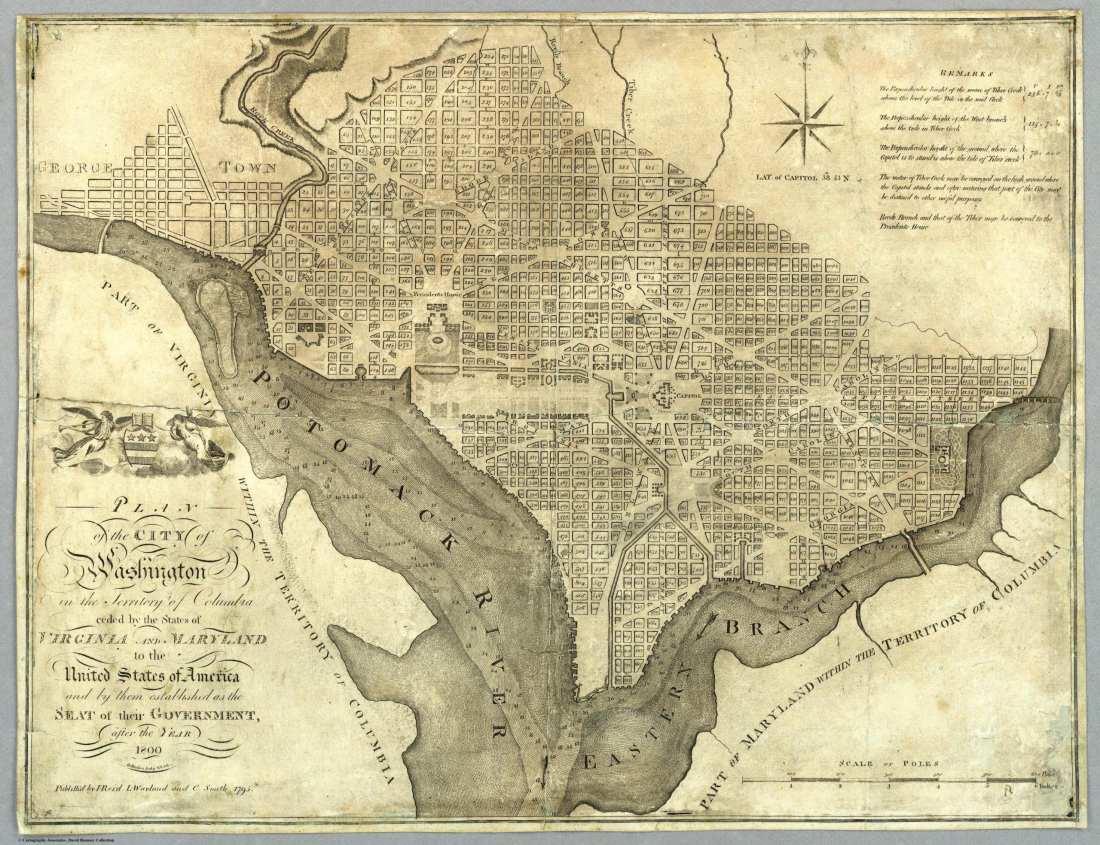

But we wish to look at the case of one elderly American man who came down with a sickness right before Christmas one year. He had been outdoors, on horseback, for several hours in snow, sleet, and freezing rain. When he returned home, he had a chill and took to his bed. When he awoke early the next day, he was feverish and shivering and complained of shortness of breath. His wife called a doctor to come to the elderly man’s bedside. Eventually, three different physicians were summoned, and they all agreed that the patient required a bloodletting.

Over the next several hours, the medical team took almost half a gallon of blood from the patient. They also gave him an enema and induced vomiting. All of this only weakened the sick old man even more. Believing that they had simply not taken enough blood from him, the doctors opened another vein and siphoned even more blood. By the morning of the second day of after coming back from the exposure, the old man succumbed to his illness…or, perhaps, he had succumbed to the extreme loss of blood because of his doctors’ treatment. It was 10 o’clock, December 14, 1799. He was buried four days later.

Of course, today, we know that the man probably would have survived the illness if his doctors had not practiced the bloodletting. This is a case of a patient probably being better off having never seen a doctor, let alone one that practiced this barbaric therapy.

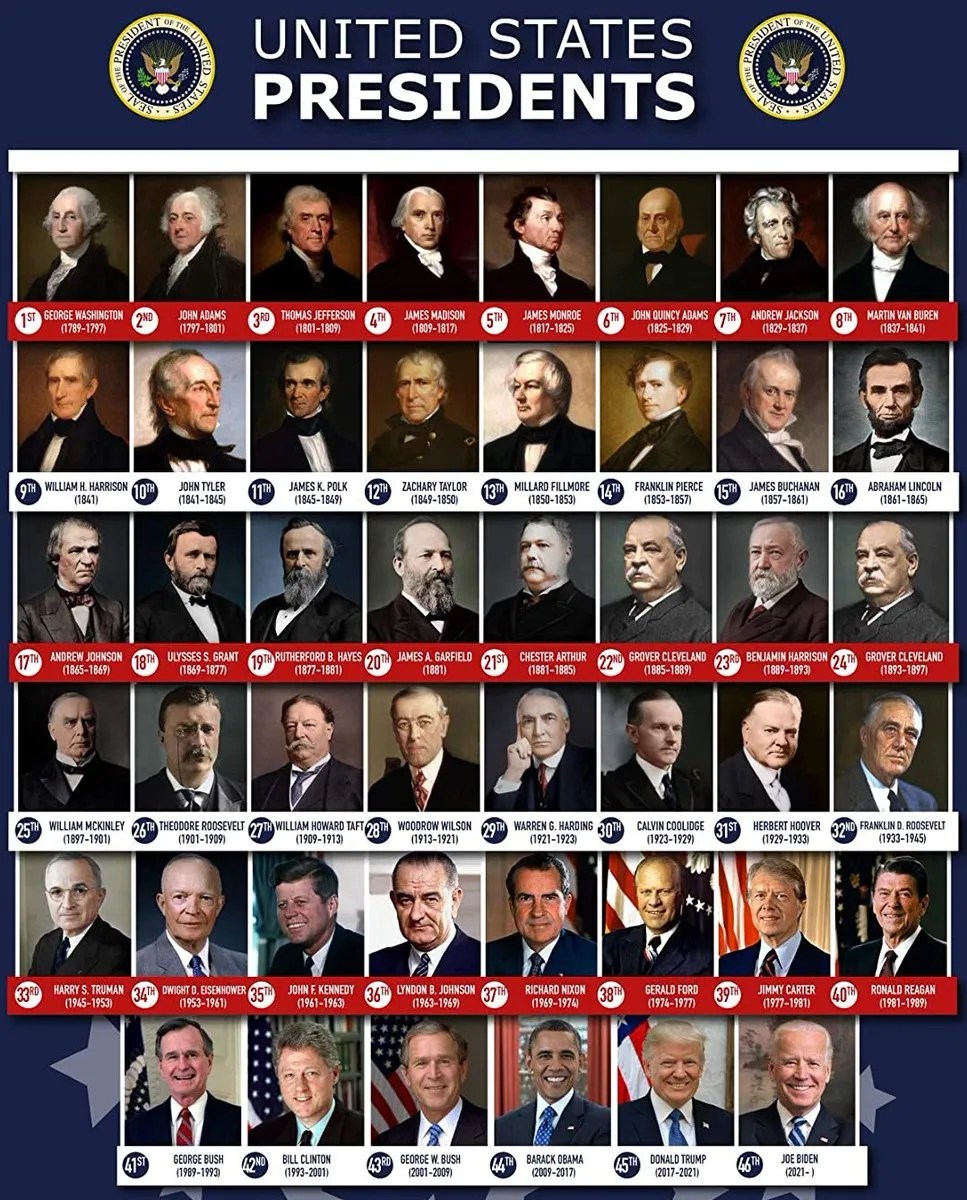

But, while we may never know for sure, most modern doctors and scholars believe that it was the bloodletting that killed George Washington.