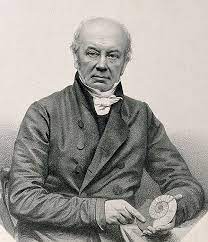

William Buckland was a distinguished man. By profession, he was a pastor, a rector, and a religious lecturer. By way of hobbies, he was a paleontologist, a fossil collector, and a publisher of scientific papers on the age of the earth. However, what many today remember Buckland for is for being one of Britain’s great eccentrics in a nation that is not short of people of that ilk.

Buckland was born in the late 1700s in the English area of Devon. From an early age, he collected the fossils that lie everywhere in that area of his birth. While such an interest as a young man might make one think he would become a geologist or scientist, he decided to follow in his father‘s footsteps Thus, he went to Oxford, and there he trained to be a minister. Eventually, he received advanced degrees in theology, but his passion was really the fossil record, and that’s what he is mainly remembered for today in the professional realm.

One of the major areas where Buckland made his reputation was in determining for himself that the biblical record of time did not match the paleontological record. He realized pretty early on in his amateur study of the fossils he found that there was no reconciling the Biblical view of a Young Earth like most theologians espoused during that period. He made a few enemies but also a few friends when he published his findings and used his fossils to back up his assertions. And while that is laudable and commendable, for our purposes, let’s look instead at how eccentric the man actually was.

First of all, he decided he was going to eat his way through the animal kingdom. I mean that literally. Buckland decided he would sample every animal that he came across or get his hands on. One author compared Buckland’s appetite to a gastronomic Noah, a man who was so consumed with consuming animals like the Biblical Noah collected them for his ark.

Now, I’m an omnivore, but the most adventurous I’ve been in my journey through the world of meat has been snake, alligator, and possum (all things that folks in the American south used to eat back in the day). But William Buckland was determined to start with the letter A and go through to Z in eating the animal kingdom–and he included most insects as well. One of his favorites was braised mice over toast. Aardvark to zebra passed across Buckland’s lips over the course of his eating exploits. He made connections with shipping companies and vessels that traveled throughout the burgeoning British Empire and hired them to bring back samples of animal he had yet to consume. And, throughout his life, we don’t know for sure how many different types of animals the man ate, but it’s safe to say that he ate more different species than any other human has.

And, you might be wondering (or, if you’re normal, you might not be wondering) at this point if William Buckland drew a line when it came to eating human flesh. I think you already know the answer to that question. It seems that Buckland was visiting the Archbishop of York in a house not too far outside of Oxford, England. The Archbishop was another one of those English eccentrics, and he collected odd artefacts–and by odd, I mean things like the locks of hair from some of Henry VIII’s wives or the finger of famous singers of the past, macabre items like that. And the Archbishop showed Buckland the heart of a man who had been publicly executed a few years earlier. The Archbishop opened the silver box in which he kept the heart, and Buckland was immediately intrigued. Could he possibly have a small taste of it, he asked the Archbishop. And the man agreed. Thus, William Buckland was able to mark “human” off his list of animals he ate in his lifetime.

Oh, and the heart?

It was supposed to have belonged to King Louis XVI of France.