Imagine stumbling upon a large complex of buildings, so vast and so beautiful, that words to describe it would fail you. Imagine architecture so complex and intricate that it surpassed anything you’d ever seen in your lifetime. Well, such a place exists in this world today. It’s visited by thousands each year, and all of the visitors come away from the encounter stunned and awed.

One of the first men from Europe to bear witness to such a place wrote of it saying, “The pen cannot describe what it is like; there is nothing like it in the world.” Another early European visitor said that something so vast and exquisite could only come from the hand of someone like Alexander the Great, or, he argued, perhaps the Romans could have conjured such grandeur but no one else.

Wrong on both counts.

Some Europeans saw it as something like an ethereal palace compound that was built for some special, holy king. Others insisted that the place was a palace constructed especially for one of the gods himself. In the early 1860s, a French explorer and naturalist said it was grander than anything designed by Europe’s greatest architects, decorated by painters and artists greater than Michelangelo, and that the entire place made all of the buildings in the rest of the world appear to be “barbaric.”

It was, and is, none of these things.

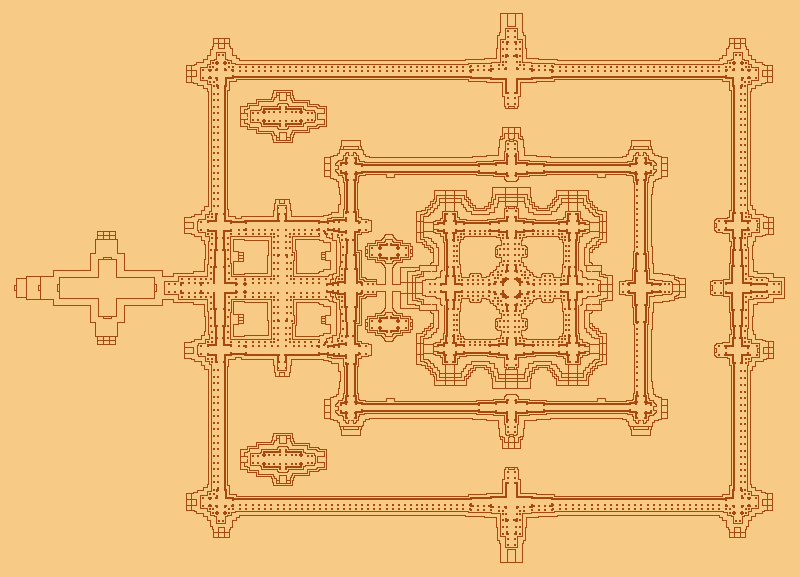

What we know for certain is that this complex was constructed using about 7,000,000 sandstone blocks. the largest of which weighs almost two tons. More stone was used in this place for construction than in all of the pyramids combined, while the area of the complex is larger than the area of modern-day Paris, France. What’s more, almost every square inch of this monstrous place features intricate carvings. It rises in parts to over 200 feet above its base, and, incredibly, records indicate that this amazing complex took place over 28 years to complete. We also know that it was constructed using rudimentary tools in the early 1100s A.D.

Yet, no one lived there. There’s not a trace of houses or household artifacts or anything used in daily living. And that is by design. The Europeans were largely clueless as to the complex complex’s purpose, the meanings of its decorations, and the intent of its planners. They didn’t realize that it was built first as a Hindu and then eventually turned into a Buddhist temple complex.

But Angkor Wat so captivated the French imagination that, under the pretext of saving the temple complex and its artistic treasures, the French government launched a military campaign that led to the occupation of Cambodia and Vietnam and the eventual establishment of French Indo-China.