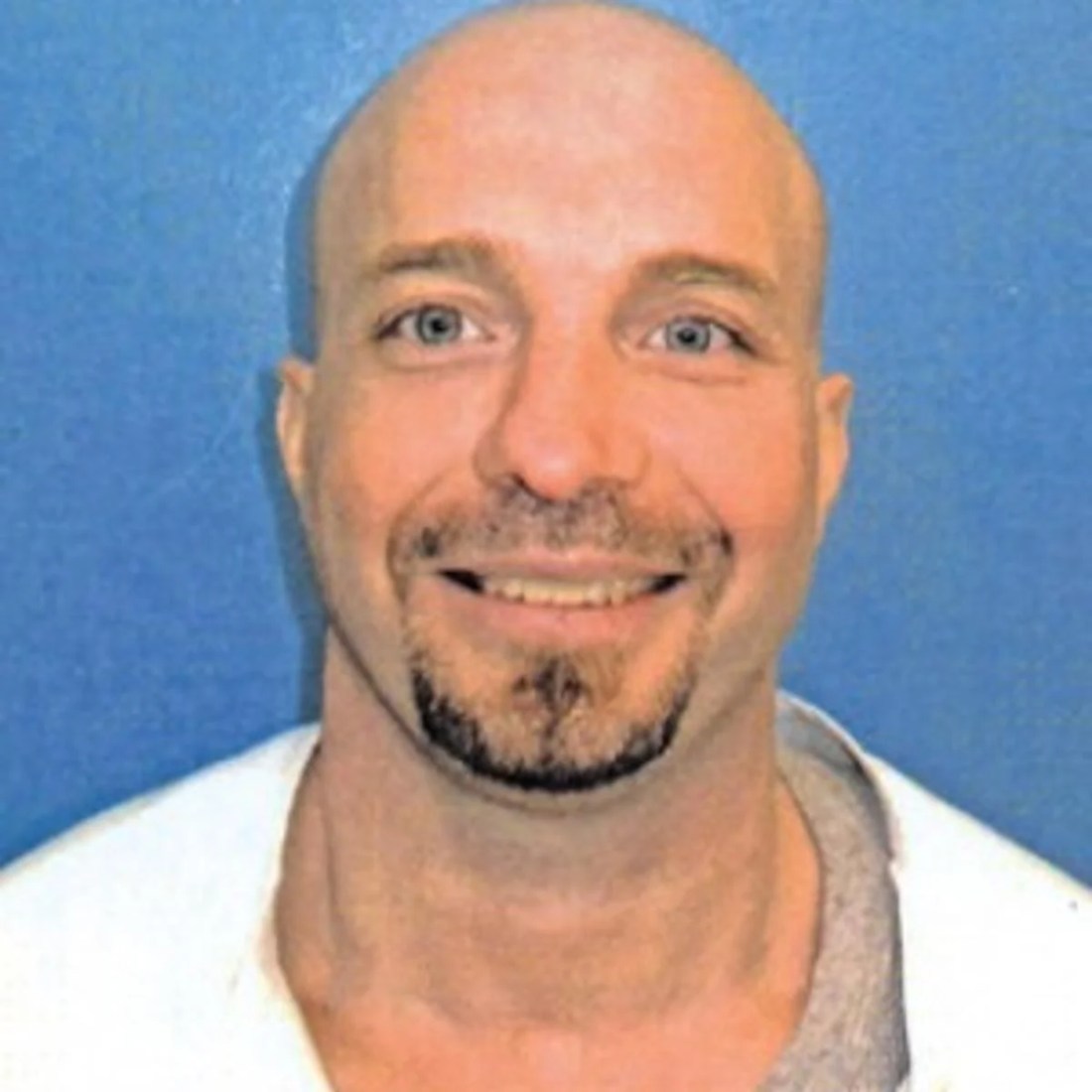

Tim Fenstermacher didn’t finish high school. Nothing wrong with that per se; high school isn’t for everyone (ditto college, obviously). Yet, Tim is today recognized as one of the best linguists in a language that is no longer spoken or written: Egyptian hieroglyphics. The story of how Tim came to be a classical scholar is long and fascinating. And it began with him writing letters to other scholars and to scholarly journals.

Take, for instance, a letter Tim wrote to Biblical Archaeology Review, one of the most prestigious peer-reviewed journals in that field. I say “a” letter because Tim has written several letters to that journal and others over the years. But the letter to which I refer called the journal’s attention to a recent article that appeared in its pages. In his letter, Tim disagreed with the conclusions drawn by one of the foremost scholars in the field, and he pointed to evidence to back up his conclusions. The scholar, a highly respected archaeologist from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, had to admit that, yes, Tim’s polite refutation of her theory and his differing assertions were correct, and her paper was revised.

Now, I have some tangential experience with this sort of thing. One of my best friends in the world isn’t a literary scholar and hasn’t devoted his life to the study and analysis of the author John Steinbeck. But, when he found some important and undiscovered information about Steinbeck and presented it to that discipline’s scholarly world, he was ridiculed and derided even though what he found was new and significant. I say all that to say that many professionals do not take kindly to amateurs, no matter what the field, telling them they’re wrong or introducing new information they themselves didn’t discover. The feeling seems to be that no one outside their field can be as informed as they; its as if these scholars are in an exclusive club, and those who either don’t have the bona fides or put in the time aren’t allowed in. Only they have the keys to the kingdom as it were. Now, please know that I’m referring to provable, demonstrable scholarship and not cockamamie theories or rhetoric.

But Tim’s scholarship was impeccable. And, despite his lack of letters after his name or any actual work in the field in Egypt, classical scholars began swapping letters with Tim and seeking him out on his thoughts about this hieroglyphic text or that inscription on an ancient Egyptian temple. How did this happen? How could a middle-aged high-school dropout become one of the go-to experts in a field that he never went to college to learn about and never dug an archaeological site to gain knowledge? Well, it turns out that Tim was self-taught. He happened to find a copy of an archaeological journal in a library one day, and something about the funny figures of the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics intrigued him. He began borrowing books on the subject. He created homemade flashcards with the symbols on them, and he poured over them daily. He got to where he could find words pretty quickly, but he had trouble translating sentences. But, one day, it all clicked. There is something in Tim that allowed him to put the linguistic puzzles together quickly. He can distinguish readily between the differing ages of the language (remember that ancient Egypt was around for thousands of years before the modern era), and he reads for context incredibly well. Some scholars spend a lifetime and aren’t able to achieve Tim’s level of fluency in the language.

Of course, Tim had plenty of time to devote to the study.

After all, what else could he do in prison?