It is the corruption of our youth, they said. The end of modern civilization, they said. That a girl–young girls–would deign to do something that would show ankles! Egad! What was the world coming to, pastors and politicians wondered. Women who did that were one step above prostitutes, it was believed. You see, 200 years ago, it was considered grossly indecent for a “proper” girl to let her ankles show in the Western World. Now, of course, lower class girls did that, be we all know what type of women they turn in to, don’t we? That is a gross indecency, that is. No, to do something that allowed a girl’s ankles to be seen by others–especially boys and men–was taboo in polite circles.

It all began, apparently, when European explorers saw so-called primitive tribesmen doing this with vines. They brought the practice back with them to Europe, and young boys in London, Paris, and other cities in Europe began doing it as well. But, rather quickly it seemed, girls took over the practice from boys. Boys went on to do other things like rugby, cricket, and soccer/football. No, girls made the exercise pretty much their own bailiwick.

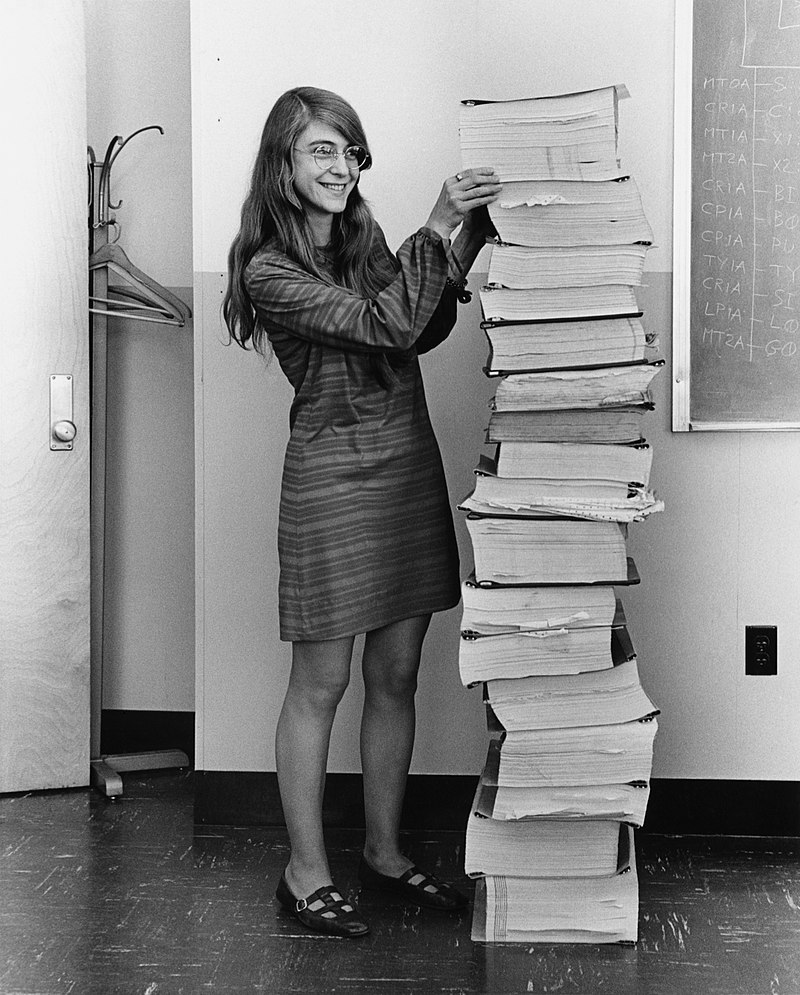

It was girls who added the chants. Girls decided the rules. Girls owned the equipment. So, the practice became their property. In the United States, as families began moving into towns, the paved streets and eventually, the sidewalks, became the place where girls practiced this exercise. The flat surfaces were perfect for it. The equipment was affordable and minimal, and almost anyone could do it.

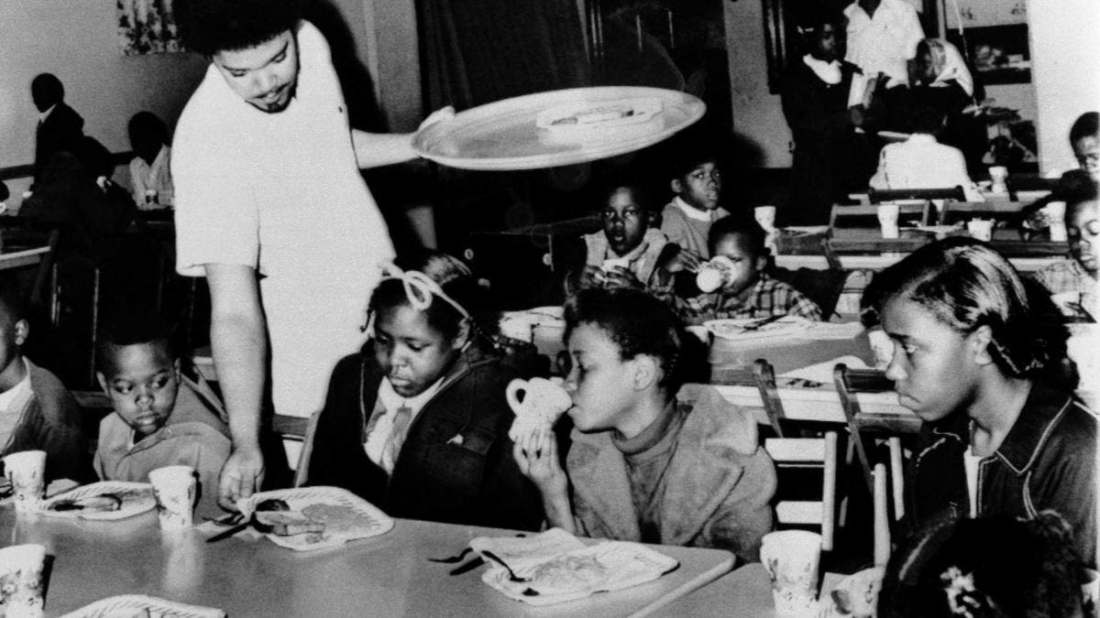

And that’s perhaps why the ministers and politicians fretted. The exercise knew no social or class distinctions. Again, it was an amazingly democratic thing that anyone could do–well, anyone with legs, perhaps. And that led to the outcry by the watchdogs of the culture. Anything that crossed social barriers and those of class and even race was seen as being radical. Perhaps all the handwringing over the viewing of girls’ ankles was only a means to an end–the end of control over the mixing of social, racial, and cultural boundaries.

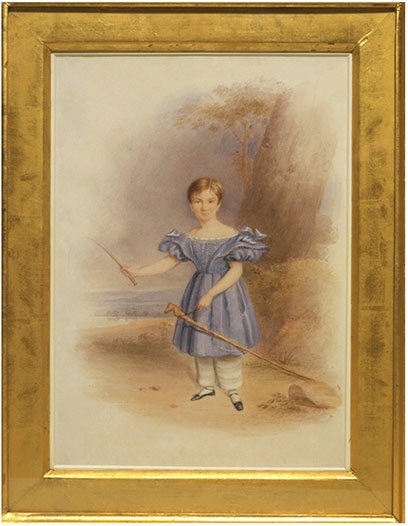

It is said, therefore, that a new garment for girls was invented because of this practice. The garment in question is the pantalette, also known by some as pantaloons or sometimes even bloomers. This undergarment went from the waist down to just below the ankle. That seemed to shut up the naysayers. They had no leg to stand on, so to speak, any more. If the girls could do this exercise and still not reveal any of their ankles, well, that was the end of the discussion.

Today, the practice is still ongoing, and it is pretty much the same as it was back in the day. You can still find kids in cities and elementary schools doing this, although with the advent of video games and other indoor activities, perhaps the popularity has taken a hit. There are local and national and even an international competition. You’ve probably done it, yourself.

The exercise in question, the one that caused such uproar and created a new undergarment for girls?

Jumping rope.