We in the west generally believe that the “free school lunch” is something that children in need should have access to in order to achieve academic excellence. That concept is fairly new in education, and there’s even some pushback in some quarters today with an increasing number of people questioning whether it is the responsibility of publicly supported schools to provide that nutrition. However, the argument has been made and the prevailing attitude is that free school lunches should be provided.

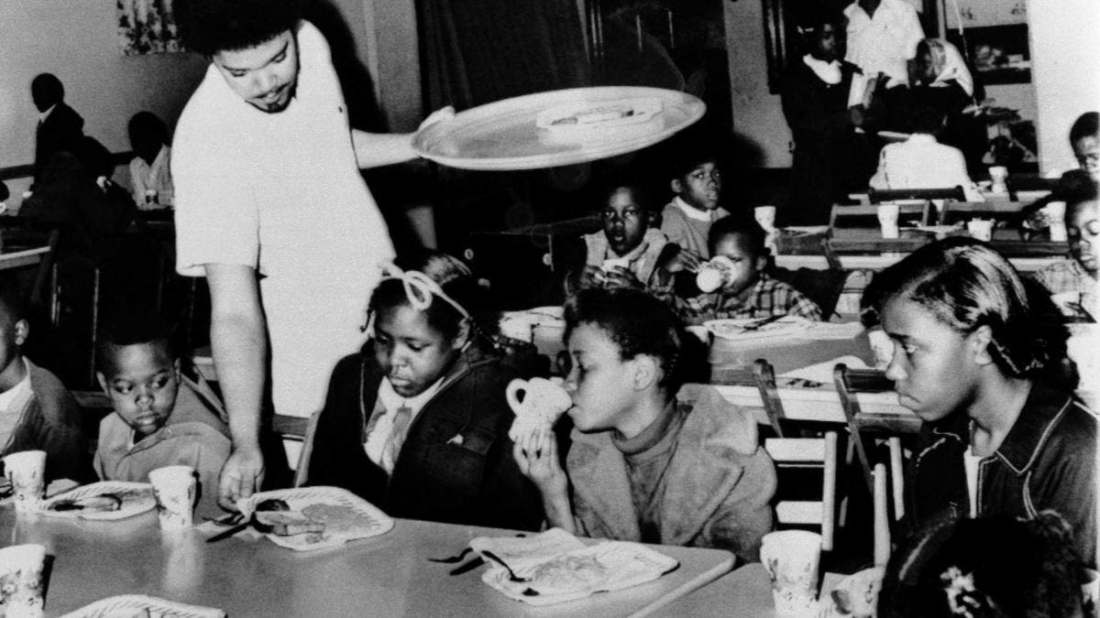

Interestingly, that type of free food program for lower income children started not because of a government program but began through a non-profit, private organization that worked in inner-city communities to better the lives of the citizens there. The first free meals for poor kids weren’t lunches, either, actually, but they were breakfasts. This group, a group that also had political goals, began serving low income kids in poorer sections of Oakland, California, in the late 1960s. They knew that people would be more receptive to their ideas if they were a positive contributor to the community to begin with. A local Episcopal Church building was used by this organization to give the free breakfasts to the kids. The volunteer group had gone to local grocery stores to solicit donations and had even consulted with nutritionists to see what types of food would pack the most punch for the kids throughout the day.

The results were astonishing.

Teachers and the school administrators reported almost miraculous improvement among their students who were receiving the free breakfasts before school. Test scores, good behavior, attendance, and over-all well-being showed significant increases. The kids were attentive as well; teachers said that the fed children stayed alert longer, they weren’t getting sick as much, and their prospects for school achievement increased. The volunteers were thrilled with their report card; they quickly expanded the program to other communities across the US. Schools in low-income neighborhoods of Detroit, Chicago, New York, and other large cities began reporting similar results to those in Oakland. The program was a success.

And that’s right about the time that the United States government began to take notice. Mainly, one agency of the federal government took umbrage with the efforts of the group. You see, the head of this governmental agency was such a racist that anything that helped minority people was seen as a threat to the nation in his eyes. He declared war on this program and its volunteers. He began ordering his offices around the nation to begin a whisper campaign against the free breakfast program. Parents were sent notices (ostensibly from the schools themselves) hinting that the group was secretly poisoning the children with the free food. And he ordered them to begin photographing the children as they left the places where they ate in an effort to intimidate the kids and pressure them to not return. The free breakfast program was shut down through this systematic harassment by the government.

What type of governmental bureaucrat–no, what type of human–would stoop so low? The program was good; it was free; no tax money was being spent, and the positives overwhelmingly outweighed the negatives here. Who would do this type of thing?

Well, luckily, cooler (and less racist) heads prevailed. Seeing the benefits of the program, the US Office of Education (what the Department of Education was before that agency was set up in the late 1970s) began offering free lunches and free breakfasts to low-income families. The program started by the volunteers in Oakland in the ’60s was reborn, and millions of low-income children have been helped.

But that success never would have happened if J. Edgar Hoover hadn’t’ve hated the Black Panther Party so much.