Margaret Abbott was an American amateur golfer at a time when “ladies” didn’t really play competitive sports. She was born in 1878 in India where her parents had moved because her father had business there. Her mother was equally accomplished, becoming a newspaper reporter and literary editor for many newspapers in the United States. And Margaret herself lived a privileged, full, and varied life before dying in the 1950s. She studied in the United States and abroad, but it was while her family lived in Chicago that Margaret first began to take golf seriously.

And she was naturally athletic. A couple of local amateur golfers (true gentlemen of the time refrained from being crass professionals, don’t you know) from the club where her parents were members took Margaret under their wings and taught her all they knew about the game. Under their tutelage, Margaret’s golf game rapidly advanced far beyond others her gender and years. She won several tournaments in and around Chicago and beyond and developed a reputation for being a fierce competitor.

Then, in 1899, Margaret and her mother traveled (by themselves! Amazing!) to Paris for the pair of them to study art. Margaret’s mother also used the time to pen a travel book for American women who had the same desire, entitled A Woman’s Paris: A Handbook for Everyday Living in the French Capital. The two women had a wonderful time, enjoying all that the fin de siècle era Parisian culture had to offer.

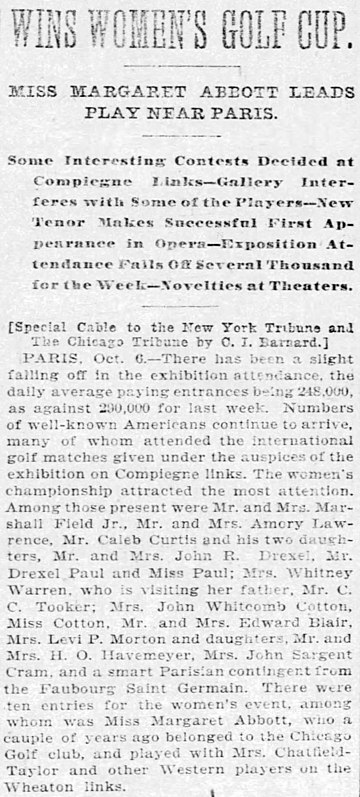

It was while the pair were in France in the summer of 1900 that they noticed a newspaper article stating that, in association with all that was going on in Paris that year, a golf tournament was open for any and all entrants. And there was indeed a great number of events happening in Paris that summer. The Paris World Fair was held that year. The French capital city hosted the second incarnation of the modern Olympics that summer as well. The city was filled with tourists from across the globe. And then here was this golf tournament. Now, Margaret’s mother was no slouch at golf, either, and the mother-daughter team decided to enter the tournament.

And Margaret won. By two strokes. And Margaret’s mother finished the tournament a respectable seventh. And, for her win, Margaret was awarded a beautiful porcelain bowl that had gilded embellishments around it. The story of this American girl winning the Paris golf tournament made the US papers, but the story was quickly forgotten.

Margaret got married eventually upon her return to the United States. She raised a family. She played some golf, but an old knee injury made her give up the sport. Almost thirty years after her death, her son, Philip, received a phone call from a professor at the University of Florida, a woman named Dr. Paula Welch. Dr. Welch asked Philip about his mother, about her life and then about what she told him of the tournament she won in Paris three-quarters of a century earlier.

Philip was surprised. His mother really hadn’t spoken much about it, he said sheepishly. I mean, he said, it was only another tournament, and she competed in many during that time. According to Philip, Dr. Welch was silent on the other end of the phone line for a moment. In fact, he wasn’t sure if the professor were still there. Finally, Dr. Welch spoke, and what she said stunned Margaret’s son.

“You mean your mother didn’t tell you that she was the first American woman to have won a gold medal in the Olympics?” she asked.