Is there anything more delicious or more dangerous that gossip? A rumor that takes wings and soars over our ears, passing from one throat to the other, each telling of the tale making the story only slightly more luscious and salacious and opprobrious. We’ve all played the whisper game in school, where a simple sentence is told to the person next to you, who passes it on to the next, and so on, so that at the end, the sentence rarely bares any resemblance to the original message.

Rose Oettinger found a way to make idle gossip pay, and pay well. But she didn’t start out that way. Rose was born in Illinois in 1881, and she wanted to be a serious journalist at a time when most middle class women rarely worked outside the home. She wrote for her local newspaper for a time after her schooling, given stories by the editor about weddings and societal events. From there, she learned how to write scenarios for silent films in the ‘teens and early ’20s. She also published a book detailing how to write for the movies. It was a modest success. Ruth then got a plumb job writing about film for a Chicago paper. She loved that work. But then, the newspaper tycoon, William Randolph Hearst, bought the paper and fired Rose because he didn’t think film warranted news coverage.

Out of a job, Rose moved to New York and continued writing about film for a paper there. Part of her job included conducting interviews of up-and-coming movie starlets and young stars, as film journalists today have to do as well. And Rose was good at ferreting out those interesting tidbits of information that the public wanted to know about their new favorite film actors. She said it helped that she was from a small town, and that gave her an advantage over her city-raised competitors. She knew what small-town America was wanting to know, and she gave it to them.

One of those starlets Rose interviewed was a lovely girl named Marion. Like Rose, Marion came from fairly humble origins. She had been a chorus girl on Broadway for a time before her big break came and she was able to star in a feature film. Sadly, most film critics panned Marion’s performance, a mark that could have been a career killer for a new starlet. But Rose liked Marion from the get-go, and the two became good friends as a result of the interview Rose conducted. When she wrote her article about Marion’s film, Rose told people to give the girl a chance, that she saw great things for Marion’s future. Because of that glowing interview, the film producer who had backed Marion’s film became a cheerleader for Rose’s writing career. That patronage led to Rose being given a job writing about film for a newspaper in Hollywood at the rate of almost $2000 per week in today’s money.

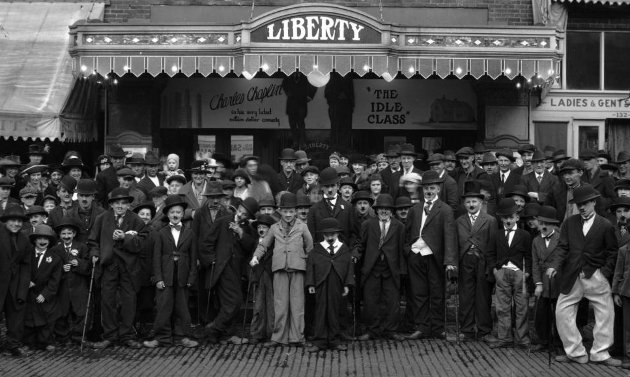

Then, in 1924, Rose was invited on a short trip down the southern California coast on a private yacht, the Oneida. Onboard that boat on that trip were some famous people, including the legendary Charlie Chaplin, famous (at the time) producer/director Thomas Ince, and Rose’s actress friend, Marion. Something happened on that boat, but we aren’t sure what it was exactly. The result was that Thomas Ince was dead. What many people believe is that the owner of the boat, a wealthy businessman and Rose’s boss, shot Ince in a jealous rage. You see, what we know for sure is that the boat’s owner was in love with the much younger Marion. It has been speculated that the wealthy older man flew into a jealous rage when he thought Chaplin was flirting with Marion, and he shot at the silent film star but hit Ince instead. The inquest that followed said that Ince died from heart failure, but his body was cremated before a full inquiry could be made.

Whatever happened, Rose and the others on board never said. What resulted is that shortly after the trip, Rose was given a hefty raise and a life-time unbreakable contract if she would write gossipy stories about Hollywood’s stars. Rose agreed. Of course, you don’t know her as Rose Oettinger (if you know her at all). No, she wrote under her first name and her married name.

Oh, and that wealthy man who was in love with Marion? He was the same newspaper tycoon (and one of America’s most powerful men), William Randolph Hearst, who had fired Rose years before. He and Marion stayed together for the next three decades.

And, until she died, gossip columnist Louella Parsons never disclosed what really happened aboard the Oneida during that trip.