The Kongo Gumi Construction Company in Japan is an old established firm, well known throughout the country, although you’ve probably never heard of it. The firm has made its reputation as the foremost company in the construction and repair of the country’s many Buddhist temples and shrines. And one of the major characteristics of the company is that, in an age when many construction companies use modern building techniques and products, Kongo Gumi sticks to the traditional Japanese methods of temple building.

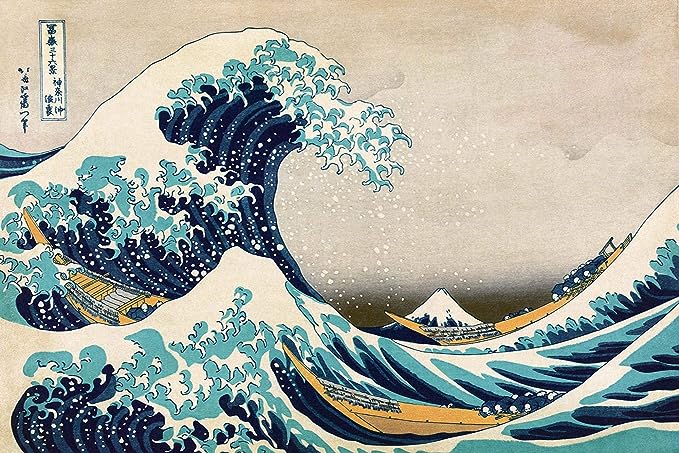

That’s important in a land where tradition is still widely practiced and respected, although it is under attack in many quarters of society. The “old paths” still carry a great deal of weight in Japan, despite the rapid incursion of a more modern sensibility and practice. There’s a famous and beautiful Japanese art print showing a tsunami wave about to rain destruction upon some Japanese boats. In the distance, Mt. Fujiyama is dwarfed by the wave. The print’s subject isn’t actually the wave or the boats but rather the symbol of the modern world crashing down on the traditional Japanese lifestyles and ways.

Thus, a cultural war of sorts has been ongoing in Japan for some decades now between the new ways and the old. And Kongo Gumi was one of the old firms that still clung to the old ways, stubbornly and tenaciously so. Sadly, their share of the construction market is shrinking as clients look for ways to save money in building, even in the building of temples. Concrete and modern methods have increasingly replaced the way Kongo Gumi has practiced their craft for a long time.

There’s an irony here as well. It seems that this old established firm was actually the one who pioneered the use of concrete in the building of temples. However, Kongo Gumi never used the material on such a scale that you’d notice it from the temple exteriors. But other and much newer construction companies have used concrete almost to the exclusion of all other construction materials. And, as the population becomes more and more “modern,” people care less and less about how a temple is constructed. As a result, the market share that Kongo Gumi held dwindled and dwindled over the years. Finally, in 2006, the company went bankrupt. It was purchased by a large conglomerate, and the traditional processes used by the firm were kept by the large company for specialist projects like temple repair or small temple construction for clients seeking that old style of building.

And that’s a sad thing in one sense. True, time marches on. Life is change. But there is something to be said, I think, about embracing the change while still remembering and appreciating the way things were done in the past. The future may depend on finding a balance between the two.

Still, it’s a shame that a company like Kong Gumi is not what it was. Especially considering that it is an old established Japanese firm, especially since it was the world’s oldest firm, established in 578 A.D.