Conrad Haas should not have been a pacifist. Given his position in the Austrian Army’s artillery corps, Haas spent most of his adult life figuring out how to best use gun and cannon fire to kill large numbers of troops. And, during the time that Haas lived, artillery killed more soldiers than any other type of weapon did.

Haas was born in Vienna and raised in a middle-class family. He studied artillery in college, and became an army officer in charge of munitions for the entire Austrian Army soon. When it came to artillery, Haas was somewhat of a savant. He not only could calculate distance and elevation of the weapons to fire accurately, but he also knew how to best conserve fire and make it effective when it counted most in battle. Such skill soon made him known throughout Europe, and he was invited to Romania to teach in an army artillery school there.

Now, you’d think that a person who knew about how to effectively cause death and destruction through artillery wouldn’t have many qualms about his job, but Haas did. In fact, he began to see that his job was that of a sort of artillery grim reaper, a person who sowed disaster and mayhem. And that made him become a pacifist while he was still in the employ of the military.

He began to tinker with the artillery and the calculations needed to shoot projectiles long distances. And this led him to try to see another possible application for artillery than that of death. What Haas came up with was revolutionary for his time. In addition, he began writing treatises about disbanding and disarming the military. “Mankind should pursue peace and not war,” he wrote. “The day will come when the powder will stay dry, the leaders will keep their money, and the young men will not die.” You can imagine that these types of writings made him some powerful enemies.

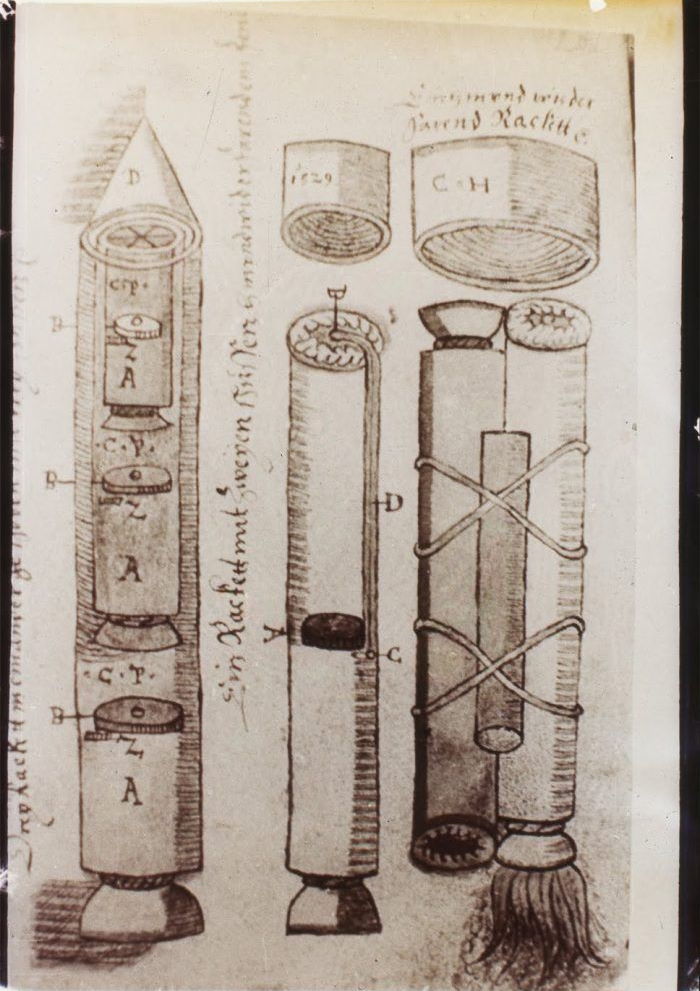

And those enemies would have done something about this artillery officer cum peacenik if what Haas proposed to do with artillery didn’t interest them so. You see, it was Conrad Haas who first came up with idea of launching not an artillery projectile, but, rather, a rocket into space. His concept was a three-stage rocket made up of a combination of solid and liquid fuels that would help the rocket break the earth’s gravity and cause the projectile to soar into the upper atmosphere.

He also came up with what is called a delta-shaped fin (the types we see on rockets today) and even a cone-shaped exhaust that would focus the power more directly and in a less diffused manner. And we can imagine that armies certainly liked the military capabilities that Haas’s ideas brought. So, his pacifism was ignored.

Of course, when Haas thought of all this, the practical application for such technology was years away.

After all, it was the 1550s.