It’s no secret that Australia was started in part as a penal colony. While Captain James Cook first stumbled upon the land in the 1770s, it wasn’t until January, 1788, a group of almost 800 prisoners from Britain arrived in an inlet on the Australia coast called Botany Bay. The majority of these convicts were considered to be “irredeemable” by the society in their home, and sending them away to the largely unsettled Australian colony served several purposes. Obviously and most importantly, it got rid of these people who were considered to be a danger to society. The other and almost equally important consideration was that the prisoners would be able to carve out a niche in the British-controlled continent.

And it was backbreaking work that these prisoners did. They found that the tools given them by their wardens were inadequate to the task. The wood, for example, was much more dense than that of the trees back in England. The native peoples resented their presence. There was sickness. The water was bad. Oh, and they were thousands of miles away from anything they recognized as normal or usual.

The man in charge of this immense task was Admiral Arthur Philip. He was actually a fair man for his time, unusually enlightened, and worked tirelessly despite all the issues concerning discipline, health, and short supplies. And, to exacerbate the situation, two other large shipments of convicts soon arrived and were put under Philip’s care.

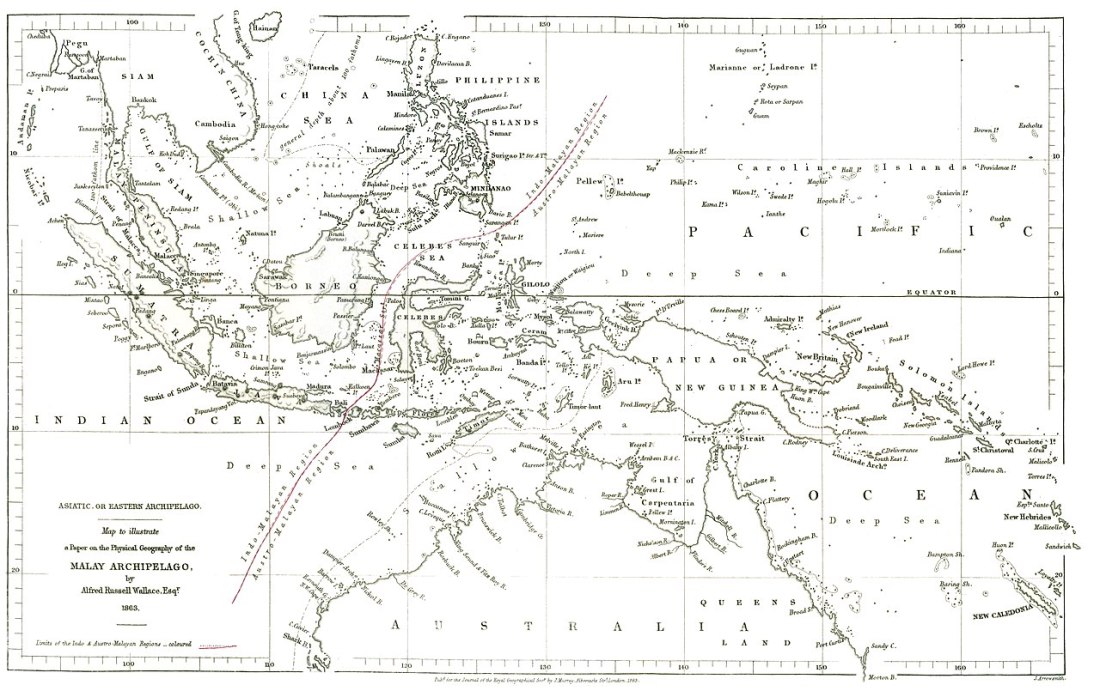

Now, Britain wasn’t the only European nation to use another land as a repository for criminals. You’ve probably heard about Devil’s Island off the northeast coast of South America and French Guiana that was started a few decades after Australia had been set up. And there were other penal colonies set up by other nations as well. The idea, again, was that those who committed crimes were somehow “infected” with mental disorders and not fit to be around “normal” people.

But, unlike most of the other penal colonies, the British experiment in Australia worked to move the convicts out of their incarceration and into being productive members of society–even if that society was among other former prisoners. Philip worked to set up a series of benchmarks that would allow the convicts to transition to becoming landowners and farmers as the colony grew. By the time he left to return to Britain several years later, he had set up this system and had proven that it was working. Today, several streets and landmarks and even towns are named in his honor. The work established and overseen by Admiral Philip paved the way for formal settlement of Australia. Today, we can say that about 20% of Australians can trace their ancestry back to one of these early convicts who made the journey from Britain to Botany Bay.

What we often overlook in the settlement of Australia and the first forays into establishing a colony there is that it owes its success in many ways to what happened in America on July 4, 1776. Now, you might be wondering what American independence has to do with the settlement of Australia.

You see, Britain had no choice but to use Australia at that point. Before then, when Britain wanted to send convicts away from the general population, they shipped them to Georgia–the original British penal colony.