There’s no doubt that Christer Pettersson lived a difficult life filled with the results of mental issues. Born to a middle class Swedish family in a suburb of Stockholm in 1947, Christer had a fairly average childhood. He wanted to be an actor, so he attended a high school that emphasized the performance arts. Unfortunately, and for reasons we still aren’t quite sure about, Christer suffered a head injury. To fast-forward to the end of his sad life, Christer died from a brain injury he suffered as a result of a seizure in 2004. The question is: Did a seizure cause the original brain trauma or did it result from it? We don’t know. What we do know is that this once-promising acting student completely changed personalities after the first head injury. He became sullen, withdrawn, and began taking hard drugs. His family had to separate themselves from him because of his sudden outbursts of anger and sometimes, violence.

Those outbursts became more frequent the older Christer became. In 1970, he stabbed to death another drug user, a man who, like Christer, had taken to living on the streets of the Swedish capital city. The part of the city where these men lived was an area where several film and stage theaters were located. The authorities knew that the area wasn’t safe and that most of the homeless population suffered (and still suffer) from emotional and mental challenges. As a result of his mental issues, Christer received a manslaughter charge and was forced to undergo psychiatric care as a result of the killing. Two years after his conviction, Christer was released. He returned to the theater district and to living on the street. He began a life of petty crimes and burglaries to finance his drug use. The violent episodes continued, and he was in and out of police custody.

Then in 1986, Christer later said he had a dispute with a drug dealer who had cheated him in a drug deal. He vowed revenge and told the man to watch his back. Now, we don’t know if this was the case or not. Christer often imagined that people had wronged him when they didn’t. However, given that the man was a drug dealer and that Christer was a drug user, the likelihood that something bad one way or another had indeed occurred between the two is high. And Christer made good on his promise to get the guy who had wronged him.

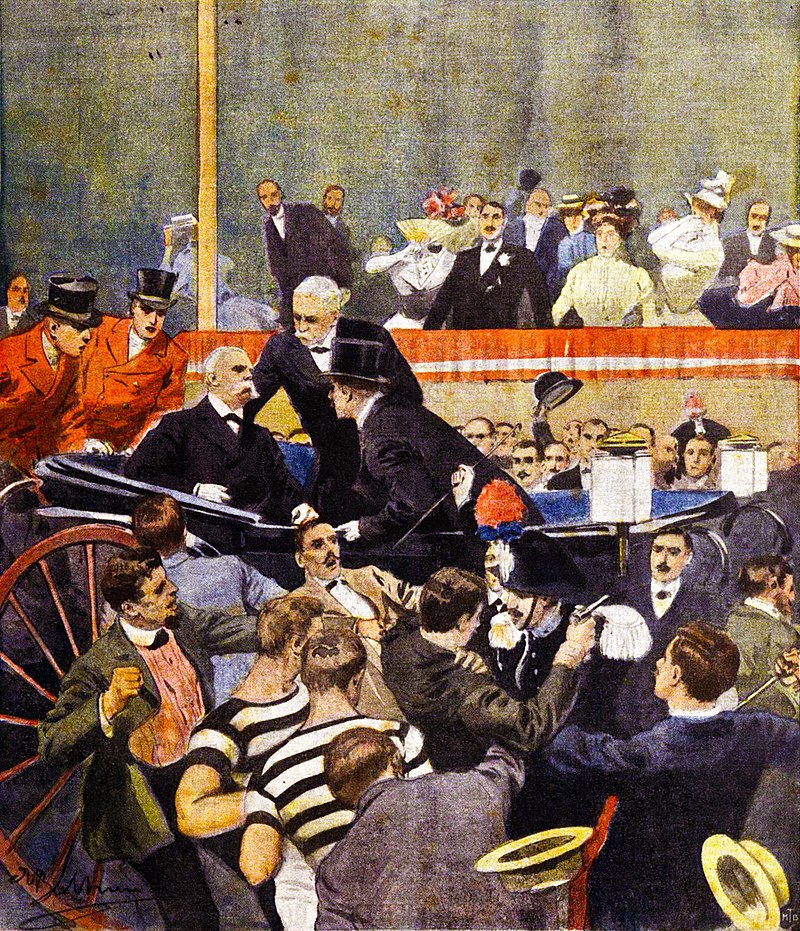

He saw the drug dealer and a woman walking on the street at the corner not too far from a movie theater late one night. The couple was holding hands as they walked, and, to hear Christer tell it, this angered him even more for some reason. Taking a gun he had gotten illegally and kept on him for protection on the streets, Christer quickly walked up behind the pair and shot twice. He hit the man in the upper back and only grazed the woman. Christer then jogged off ahead of the couple while bystanders ran to help the victims. Within 30 minutes of the shooting, the man was declared dead. The woman’s injuries were superficial and she made a quick recovery. From some general eyewitness accounts, Christer Pettersson was taken into custody as the prime suspect. However, by that time, there was no gun found on him.

Yet, despite the lack of physical evidence tying him to the murder of the man, Christer was picked out of a ten person lineup by the woman who was also shot. He was convicted of the murder of the man largely based on her testimony. However, upon appeal, the lack of a murder weapon and any physical evidence weighed heavily. Besides, the woman’s ID of Christer in the lineup had been somewhat tainted because the other nine men in the lineup were well-dressed and clean, while Christer was presented as he was picked up from the street–dirty, messy, unshaven, an still a little bit high from having gotten some drugs the night before. As a result, his conviction was reversed on appeal, and he was released.

And, as we saw, Christer died from head trauma suffered when he fell after having a seizure in 2004. Many people still think he was the one who killed that man on the street corner that late night in 1986. We still don’t know for sure, despite some talk that he had confessed to some others that he did the shooting. But it turns out that Christer also said that he was so high that he mistook the man for the drug dealer he had his disagreement with. That means, of course, that the man Christer shot wasn’t the drug dealer at all.

No, the man who was murdered on that street corner that night–maybe by Christer Pettersson–was Olof Palme, the Prime Minister of Sweden.