We’ve looked at several odd museums over the course of this blog. There was the one that featured the pair of pants made from human skin in Iceland. Remember the book library/museum in Norway that will eventually house only 100 books? Then there was the place that showcased the red ruby slippers from Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz. This time, it’s a museum in Suwon, South Korea dedicated to, well, poo.

Technically, it was a house that once belonged to the former mayor of the city, a man named Shin Jae-Deok. And, after his death in 2009, the city decided to make his house into a shrine to the man and to his most famous and significant contribution to the city–the improvement of the city’s toilets. Shin had made it his life’s work to make the removal of human waste a better experience for all the citizens of his city. And he succeeded. Thus, it seemed prudent and fitting to turn his home into a celebration of that life’s work.

So, you’ll find exhibitions on both historic examples of commodes as well as the most modern and sophisticated models. In fact, the whole litany of toilets can be found there. You can find out the effects of toilets on culture throughout the centuries (whose life isn’t complete without this knowledge?). The inaugural meeting of the World Toilet Association met there a few years ago. In fact, they were the major sponsor of the building of the museum. The impetus for beginning the museum was also the declaration by the United Nations of the International Year of Hygiene.

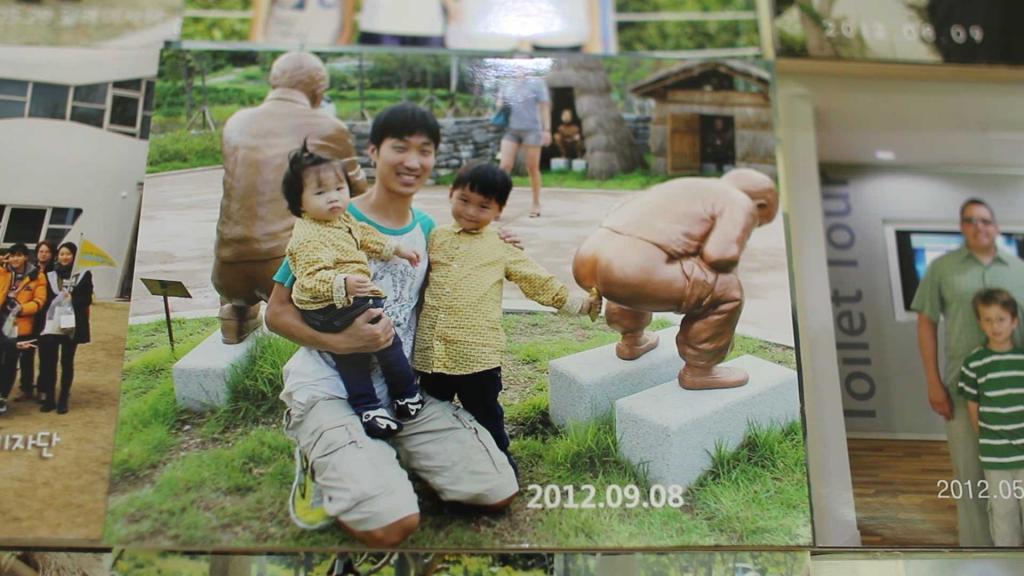

Now, I know you’re looking at the calendar and thinking that it’s way, way too early for April Fool’s Day. But this museum is no joke. In fact, besides the exhibits inside, the land surrounding the house has been rebuilt with more, well, interactive exhibits. Sculptures adorn the grounds, and they depict various human figures in the act of elimination, both liquids and solids.

I don’t want you to get this South Korean museum confused with the toilet museum that’s located in Delhi, India. That particular museum is more dedicated to the sanitation issues in India specifically rather than the world-wide problem of how to make a better crapper. And don’t forget that there’s a similar permanent exhibition in Kyiv, Ukraine, but, because of the situation with Russia right now, that museum is closed. That Ukraine one does have the world’s largest collection of chamber pots, but, again, the South Korean museum is better because of its wide-ranging nature of the cultural aspects of pooing.

By the way, the name of the museum is, in Korean, Haewoojae. Translated, that means “House of Relieving Anxiety.” Apropos, don’t you think?

So, if you find yourself in Suwon sometime, do yourself a favor.

Go.