Historically in the United States, same sex relationships have been against the law from a legal standpoint, sin from a religious standpoint, and an unspeakable offense and/or a mental derangement in the social realm. Yet, all of that never stopped same sex couples from existing and even flourishing throughout American History.

Now, of course, these were not relationships that were generally out in the open; there was no flaunting of sexual orientation because of the backlash such behavior would cause in the law, church, and society at large. And people created euphemisms for men who lived with men and women who lived with women. If two women were life-partners, many times that was referred to as a Boston Marriage. Wellesley College near Boston was where women of the upper middle and upper class would go to receive an education. Being women of some means, these Wellesley students weren’t as dependent on men for their livelihoods and preferred the company of other women. So, they would cohabitate, and that’s where the sobriquet sprang from. Now, to be fair, some of those Boston Marriages were not sexual in nature, but the living arrangement certainly went against the norm for that time period. For men, the euphemisms were a bit more subtle. Up until the past few decades, if a gay man died, his obituary would often list a “friend” or say that he was “a life-long bachelor” or “he never married,” and those in the know would be able to read between the lines.

Let’s take the case of a devoted couple who lived not too far outside of Baltimore, Maryland, about 175 years ago. Let’s call them Aunt Fancy and Miss Nancy, because that’s what people who knew them called them. The pair lived together for some years, and they would be seen at social functions together, even at gatherings where it was understood that the spouse or significant other was supposed to make an appearance. They also managed to work in an occupation that would normally not be acceptable for people with same sex attraction–the government. And that work often separated the two. The letters we have found (most were destroyed by their embarrassed family members after the couple died) that the pair exchanged were long and expressed, passionately, how the other one was terribly, terribly missed.

It’s rather interesting that Nancy and Fancy would’ve gotten together in the first place. Nancy was from Pennsylvania originally, while Fancy hailed from the Cotton Belt of Alabama. It was amazing that they ever got together at all. Nancy had even been engaged once, but the wedding was called off when the fiancé died suddenly–much to Nancy’s relief, a later letter would admit. And, like the examples of other couples as in the Boston Marriages, they both came from money. But their personalities were different; Fancy was, well, fancy; a quiet and refined gentility oozed from every pore and hair. Nancy was loud and boisterous and enjoyed a bit of a drink every now and then where frivolity would ensue. Yet, the relationship worked for many years. Writing to a relative while waiting for Fancy’s return, Nancy confessed, “I am now solitary & alone, having no companion in the house with me. I have gone a wooing to several gentlemen, but have not succeeded with any one of them.”

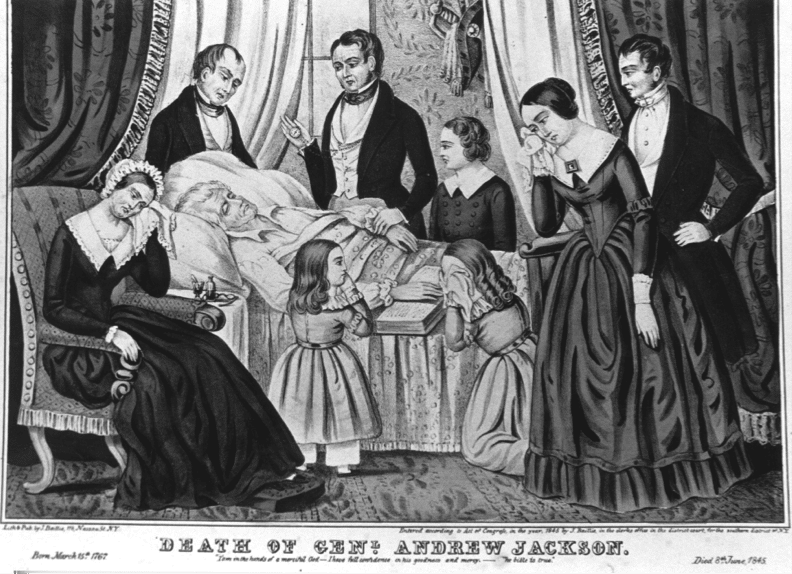

Sadly, Fancy died in 1853 of tuberculosis. Nancy would follow 15 years later. Oh, and their names? Those were the names that they were called in derision, first given to them by none other than Andrew Jackson. While we don’t know for sure if the nature of the relationship between the two was sexual, we do know that some of their contemporaries and political foes and even friends certainly thought so. You see, you know Aunt Fancy as William Rufus King, who was the Vice-President under Franklin Pierce, and you know Miss Nancy as President James Buchanan himself.