I’ve been thinking about the Butterfly Effect lately–the idea that one small, seemingly insignificant event can trigger other things that lead to a major change in the world. As an amateur/armchair historian, playing the “what if?” game can be both fun and scary. What if Bobby Kennedy hadn’t been shot? No Nixon/Watergate then, no ending in Vietnam like we had it, possibly things like universal healthcare in the US, etc. And so forth.

Take the life of Gaetano Bresci, for instance. You’ve never heard of him, and neither had I, really, until I followed him down an internet rabbit hole search recently. Bresci was an Italian immigrant to the United States in the late 1800s. He settled in Hoboken and then Patterson, New Jersey, and took up with another immigrant, an Irish woman, with whom he had two children. Bresci worked as a silk maker in a mill there, and he became interested in making a better life for himself and his fellow workers. Thus, he began attending meetings of labor unions and workers’ organizations to see what could be done collectively to improve working conditions in the factories that dotted the New Jersey landscape.

But he quickly grew frustrated. The meetings were much talk and little action. “Much ado about nothing,” he remarked, and he began to think of ways that he could have an impact. You see, Bresci had a soft heart in one sense. He saw injustice in the way workers were treated by management–harsh conditions for little pay, no breaks during the day, huge profits for the factory owner on the backs of the workers, etc.–and knew that the system was inherently unfair. But what could he do to change it all? He was only one person, after all. You can understand his frustration.

Then, word came about an event back in his native Italy. It seems that some desperate factory and farm workers in Milan had rioted because they had no food. The Italian government stamped down, hard, on the rioters, and several dozen were killed and over 400 wounded when the military opened fire on their own citizens. This outraged Bresci. He purchased a pistol in New York, kissed his wife and children goodbye, and returned to Italy. He was going to act.

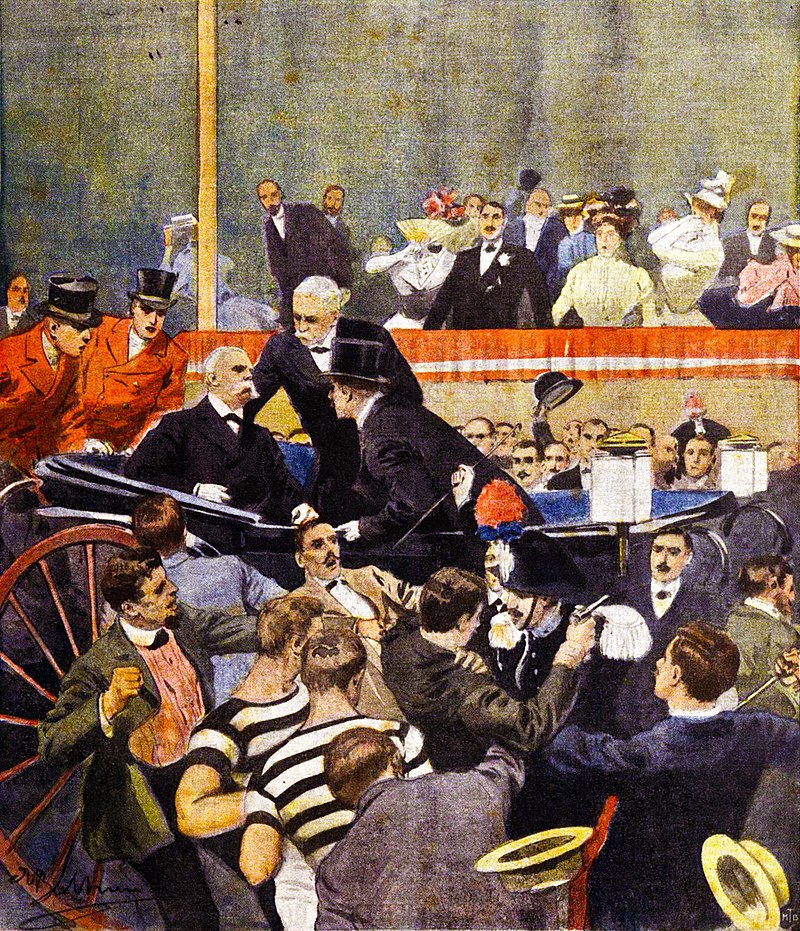

On July 29, 1900, Bresci stepped out of the crowd that surrounded King Umberto of Italy and shot him, dead. He then did not resist arrest, and he calmly stated that he had not killed a person but, rather, he had killed a principle. Well, of course, this “reason” for the assassination was seen as preposterous, and he was sentenced to life in prison. Shortly after being incarcerated, he was found dead in his cell–possibly killed by another, unknown assailant.

Back in the United States, the press hailed his death. Such should be the fate of anarchists and assassins, the newspapers said. But one young man, a Detroit-born fellow of Polish descent born Leon Czolgosz but who called himself Fred Nieman, saw Bresci as a hero. Here, he thought, was someone who was willing to do a wonderful thing to strike back at the people who held power and who exploited the little fellow, the nobodies of the world. Nieman, by the way, was the name chosen by Czolgosz because it means, literally, “nobody.”

So, inspired by the Italian assassin, Nieman took a pistol, wrapped it up in a bandage on his hand, went to the Buffalo World’s Fair in 1901, and shot and killed American President William McKinley. A nobody who killed a somebody.

But let’s Butterfly Effect this. Who became president upon McKinley’s death? Theodore Roosevelt. If McKinley had lived, then there might have been no Progressive Movement as we know it; no election of Taft in 1908; no splitting of the Republican vote in 1912 that led to the election of Woodrow Wilson. And if Wilson isn’t elected, then there’s no entry by the United States into World War I. And possibly no victory of the Allies in that war. And if Germany doesn’t lose, then no rise of Adolf Hitler in the early 1930s.

And no Hitler?