If email had existed years ago, here’s a possible, mostly historically accurate, but completely imagined inter-office communique:

To: Senior Staff

From: JM

Date; 20 May, ’92

RE: The Boss

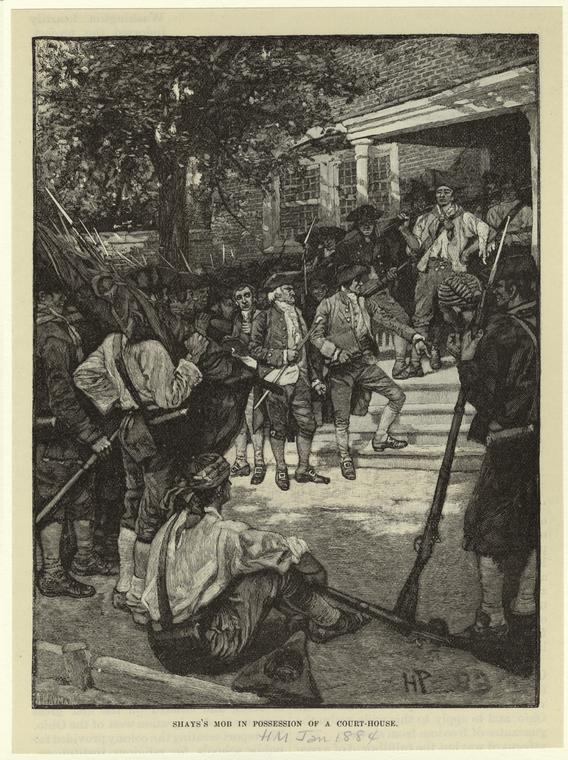

He’s talking about retirement again. We are at a juncture where such a move would prove disastrous for our little enterprise. In talking with him at length in his office this morning, the following items were brought up as the major reasons for leaving.

1.) He’s tired. The years of strain of being an exec have taken their toll, he says. He feels that he’s done all he can do to get us off the ground and on as stable a footing as he can given how little time we’ve been in operation, but he argues that he’s got nothing left to give. He talks about staying home, working in the garden, taking walks along the river, and playing with the dogs. Can you believe it? The dogs, for Chrissakes. And he says his wife is tired of him not being home after so many years of work. He says he’s old–but he’s only 60! For those of us who’ve been here since before the start, he’s always seemed older, but he’s never seemed old to us. We’ve got to remind him that he’s young, that he has many productive years left, and then say things about how his color is good or how he’s looking well.

2.) He’s fed up with the interoffice politics among senior staff. That’s why this email if for your eyes only. It would do no one any good to learn about infighting among the senior-level employees. Keep this to yourselves. But he’s looking specifically at Al and Tom. You guys have your issues, we know, but you’ve got to keep that stuff out of the office. No arguing in front of him, in the halls, or anywhere on the property. If you guys have something to say to each other, say it out of earshot of anyone having to do with this office. The Boss says he’s tired of having to play referee for your infighting. And he worries that staff as a whole will choose sides between you two, leading to division within our group, and possible dissolution of what we have all (especially he) have worked for so hard for so long. He is aware that there will be fighting over who will replace him among us, but he still is wishing to step down.

3.) Finally, he’s worried that if he stays any longer in the leadership position, people in and out of the organization will soon not be able to separate him from the role. In other words, his concern is that the man will become synonymous with the position, and anyone who follows him will forever be considered and seen as the “not him.” That’s a valid position to a degree, granted, but, again, we are at a critical point in our existence. We have to assure him that if he decides to step down now, there may be no role for anyone to assume after he leaves.

We have to have a united front on this. Remember: Stay positive in his presence. Tell him how good he looks and how young. No infighting (can’t be stressed enough). Remind him how vital he is to what we are trying to do here.

Everything depends on President Washington being re-elected in November and staying in office for at least four more years.

–Madison