One of the best bosses I have had across my various jobs was a woman named Kay Tyler. She taught me two valuable lessons. One was to thing things through. What will happen each step of process? What effect will those things have on all involved and on the pursuit of the goal? The other lesson was to have not only a Plan B but also at least have an idea of Plans C-F or so. Those lessons have stayed with me and helped me be a better administrator and even a better person. Ms. Kay was a perfectionist, and she was one of those who backed up what she taught with a lifestyle to match. Another such perfectionist who is about the same age as Kay Tyler is a programmer and code writer named Margaret Hamilton.

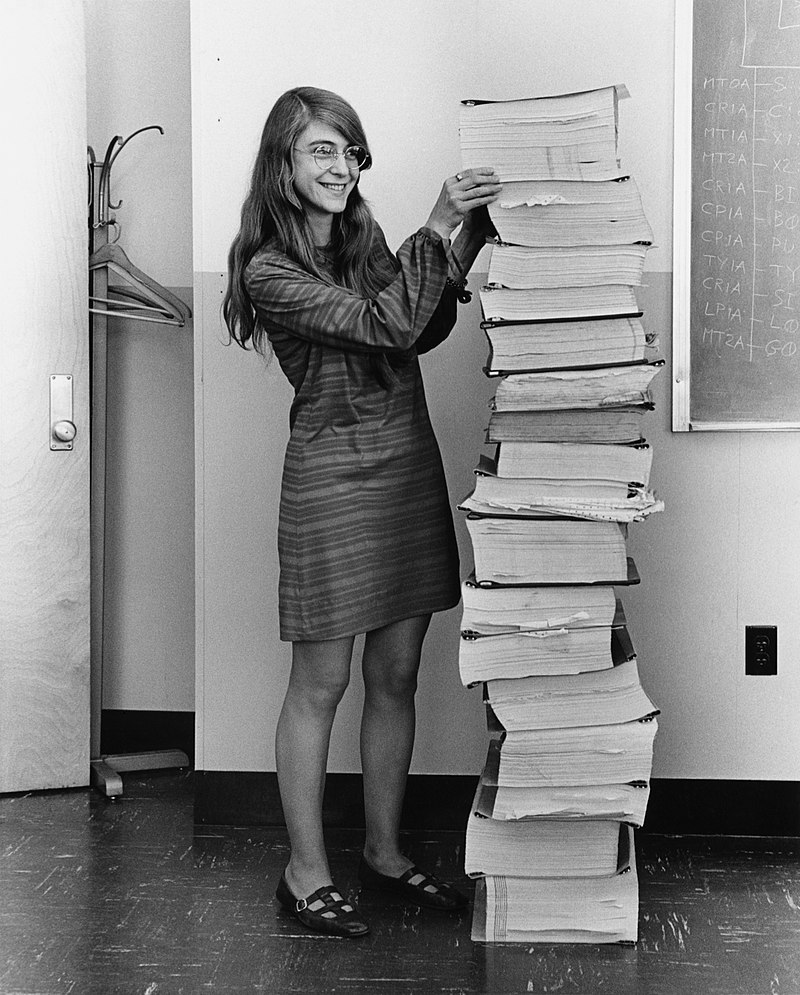

Margaret wrote computer code for M.I.T. back in the days when writing code was literal writing–by hand–each line of code on paper. Those codes told the computer what function to do next in a process. Like Kay Tyler’s advice, Margaret also had to think things through, and she definitely had multiple back up plans just in case. People would ask her, “In case of what?” Margaret would smile and answer, “Exactly!” In her capacity as a code writer, people’s lives were on the line; the decisions her code made could make the difference between life and death for some. There’s a story that, one night during a work party, it struck Margaret that one line of her code was incorrect. With her apologies, she rushed out of the soiree and returned to her office. Sure enough, one small part of a line of code was in error. Margaret realized that even something so small could make a world of difference in the right situation. So, Margaret became a perfectionist out of a sense of responsibility and ownership of her work–concepts that are becoming more and more foreign to some in the workplace today.

And remember that, during the 1950s and ’60s, it was rare for women to be in the workplace compared with today. And Margaret was also a mother. People at the time would ask her nosy questions like, “How can you work and have a child?” and “Don’t you love your family?” Yes, those were the types of things people thought about working mothers 60 years ago (not that some don’t still feel that way). Yet, despite knowing that her work was important, Margaret still felt some societal pressure to conform to the middle-class expectations of a woman being a wife and mother first.

So, often, Margaret would bring her daughter to work at M.I.T. with her. And that seemingly little thing led to something amazing. One night, while her daughter was with her in the office, Margaret allowed the child to play with one of the machines she had written the code for. The child, in her innocence, tasked the machine to perform a function for which Margaret had not written code. That piqued Margaret’s attention. What would happen, she wondered, thinking things through, what would happen if someone using her code would accidently make the same input that he daughter had done? Would that cause a catastrophic failure of the system? Should she write code that would keep the machine from even performing that operation at all, even it would be accidental? Better safe than sorry, she reasoned. So, Margaret wrote the code.

Turns out that when the code was finally used in the real world, someone indeed accidently made the same input that Margaret’s daughter had done. However, because of her sense of perfectionism, Margaret was ready for it. And, in the final analysis, it was that mentality that perhaps saved lives.

What you don’t know, most likely, is that Margaret Hamilton wrote code that produced the modern coding systems we use today. In the same way that the invention of the telegraph led to modern cell phones, Margaret’s code is the grandparent of the code used on the device you’re using to read this blog right now. At the time, of course, Margaret’s code was groundbreaking and revolutionary. And, it’s true, her code saved people’s lives.

You see, Margaret wrote all the code for NASA that sent humans to the moon.