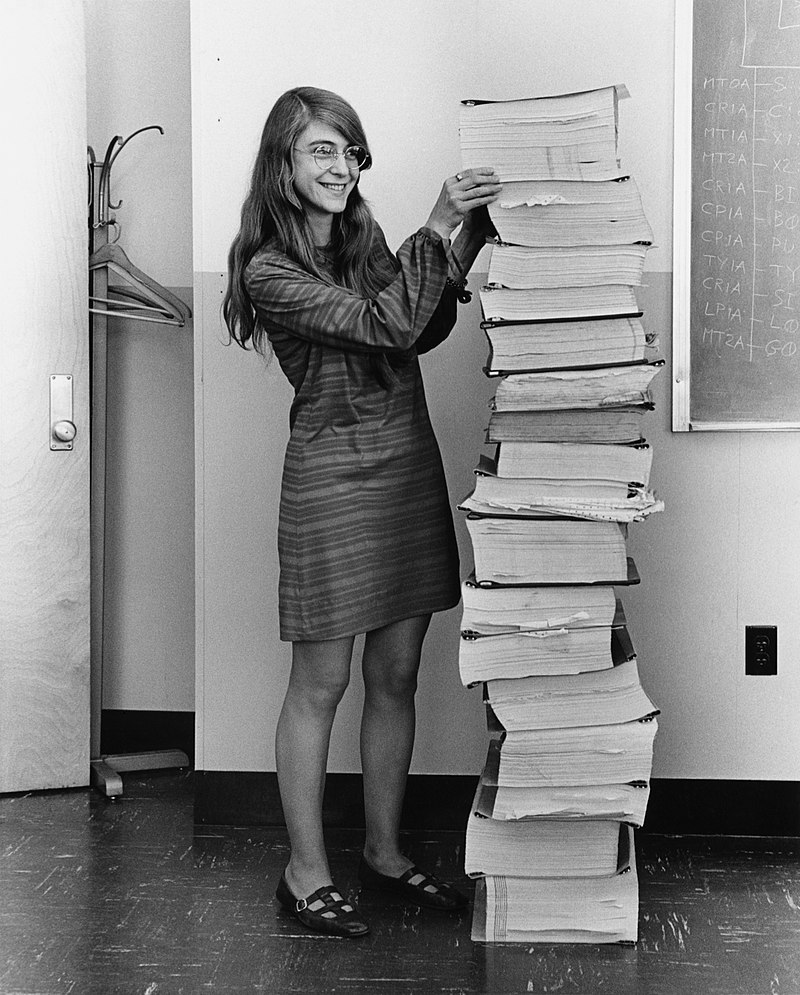

The other kids in the neighborhood and at school called him Fat Freddy

Growing up in Latrobe, PA, in the 1930s and early 40s, Freddy faced the emotional trauma of being bullied for much of his young life. Because of his weight, Freddy felt shame when the children would point and laugh. We also have to remember that being a bit chunky as a kid at that time was an anomaly compared to today. Nevertheless, his weight made him not be picked for teams when the kids got together to play, and that type of rejection along with the cruel joking from the other children combined to make Freddy’s life pretty much miserable.

Thus, Freddy spent much of his childhood in his family’s large, three-story home, playing by himself. The family was upper middle class for the town, his mother’s family having owned large store in Latrobe and his father managing the town’s brick factory. Freddy was named after his mother’s dad, in fact. When he was 11, his parents adopted a sister in part to give Freddy some company, but he didn’t interact with her much. No, for most of his young life, Freddy kept to himself in the house. He created a whole imaginary world, a safe world, a place where no one would shame him for his body size and where everyone was happy. That pretend world had princesses, kings, brave knights, talking animals, and was filled with magic and love. It was a safe place. Because of that imaginary world, Freddy became, one person later noted, best friends with himself. His toys, his puppets and miniature houses and cars, they all became his world. It’s a perfectly natural response to the trauma of bullying Freddy had suffered from his peers.

As many children do, Freddy grew out of his chubbiness as he reached puberty. By the time he went to high school, his body shape had changed. However, the shyness he had developed as a defense against the bullies remained. While the outside of Freddy appeared to be like everyone else, inwardly, he was still the kid who feared rejection and derision. Somehow, he made two friends as a freshman at Latrobe High School. One of them happened to be an outgoing and brash young man who liked Freddy for who he was and not for how he looked. That friendship helped Freddy become more self-confident. He described it as finding someone who realized that it wasn’t what is on the outside of us that counts but, rather, the important stuff is what lives in our hearts. For Freddy, that realization made all the difference.

Freddy proved to be a good student, also. He went to college and earned a degree in music, then he attended theology school and became an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church. Instead of wanting to pastor a church, it was Freddy’s idea to become a minister to young people who had endured the same types of traumatic experiences of bullying he had gone through as a youngster. Freddy could relate to them. He could speak their language. He knew what they were going through. Throughout the rest of his life, Freddy would maintain these credentials because he strongly believed that this work was his calling, his ministry. And that ministry of helping children navigate life’s traumas is exactly what Freddy did, too, almost until his death from cancer in 2003.

You’ve witnessed his ministry, most likely.

That’s because you know Fat Freddy as Fred Rogers, and his ministry was called Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.