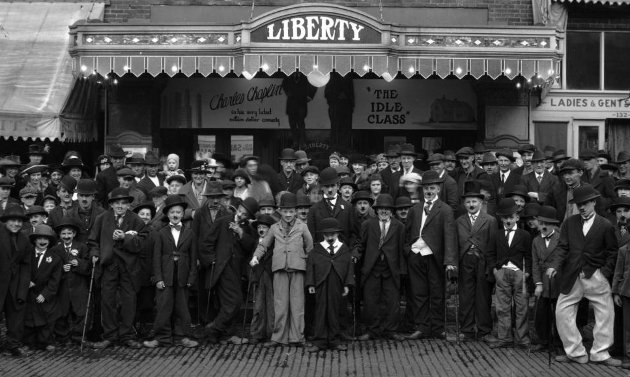

Some historians claim that a woman named Sarah Bernhardt, was the first “modern” celebrity. The French actress used popular magazines and her relationships to famous painters and writers and musicians to publicize her stage career in the 1800s. As a result, people world-wide knew who she was, thus becoming the first international star. But the world has never seen the popularity of the (mostly silent) film star, Charlie Chaplin. Everywhere he went, even when he wasn’t in his usual costume as the character “The Little Tramp,” the talented actor and director was mobbed. He was so famous in the 1910s and ’20s that cities and organizations would often hold Charlie Chaplin Look-Alike contests, contests that offered cash prizes to the person who could best imitate the character’s signature splay-footed walk. Even a young Bob Hope, later to become a famous comedian in his own right, entered one such contest during that time.

One such competition was held near San Francisco in the late 1910s as part of a county fair and a new movie theater promotion. Several dozen competitors donned their little under-the-nose bristle mustaches, put on ill-fitting hats and too-big shoes, found ragged pairs of trousers, grabbed reedy canes, and made their way to the fairgrounds. As the crowd gathered to watch the competitors, one of their number, a young man named Spencer, watched with amusement. “Those clowns,” he said to his small group of friends who had joined him at the fair that day as they watched the look-alikes start to parade across the fairground’s stage, “they don’t have the walk right.” You see, Spencer considered himself somewhat of a Chaplin expert, having seen everything that the comedian had put out on the screen.

Spencer’s chums began to goad him good naturedly. One of them dared him to get up on the stage and show them how to imitate the Chaplin walk if he knew it so well. Spencer grinned at his friend. “You’re on,” he said. “Here,” he added, taking off his jacket, “hold this and watch!” And, with that, the competition had another entrant. Spencer made his way to the side of the stage where one of the organizers was trying to corral the several would-be Chaplins in line before they demonstrated their imitations on stage.

“Say,” Spencer said to the harried worker, “d’ya think I could join the competition?” The staffer didn’t care. He just wanted to get through the warm afternoon as quickly as possible. “Sure, what do I care?” he said handing Spencer a number and a safety pin. “Just put this on your shirt and go to the back of the line.” And, flashing a large grin and a thumbs-up to his group of friends, Spencer went to the end of the queue to wait his turn. Eventually, as the last entrant, Spencer–without any Chaplinesque costume at all–made his duck-walking way across the stage. A few people clapped, mainly Spencer’s friends, and a few in the crowd booed.

The organizers used a set of three local minor dignitaries as their judges, and the judges also used crowd approval as a criteria in selecting the five finalists for the competition that day. And, when the votes were tabulated and every competitor was judged, it turned out that Spencer didn’t make the cut. He and the other unsuccessful entrants were thanked by the emcee and they were dismissed. Spencer made his way back to his little coterie of friends. They laughed at his failure, telling him that maybe he wasn’t as good of a Chaplin fan as he thought he was if he couldn’t even do the Chaplin walk correctly. Spencer was incredulous. In his frustration, he didn’t want to stick around to see who won the contest, and, with his friends still laughing at his expense, the group made their way on down the fair’s midway.

Now, of course, no one remembers who won that look-alike competition that day.

However, we do remember the contest.

For, you see, it was the day that Charles Spencer Chaplin couldn’t even win a competition imitating himself.